By: Aaron Schulman

In the first part of this series, we introduced the general overview of the acoustic guitar anatomy with a fairly detailed diagram of all of the most common working parts of the contemporary acoustic guitar. Whether you are a traveler, jamming on a Baby Taylor ¾ size acoustic guitar, a larger concert or dreadnought model, the anatomy of a common six-string acoustic guitar is basically the same across the board. In that article, we detailed how the acoustic guitar has three identifiable regions under which everything else could be recognized:

In this installment, we’ll take a closer look at the head region in a little more detail. While it is not the emphasis of this work to explain all the subtleties and nuances of the physics behind the working acoustic guitar, this series can help one get more familiar with much of the anatomical features of a common acoustic guitar. And though the shapes, models and manufacturers tend to vary by style as much as snowflakes with the proliferation of all the luthiers and brands out there, the acoustic guitar still contains some very specific anatomy which allows it to be classified in the acoustic guitar family and among other chordophone (vibrating string) instruments.

A closer look at the head inlay

Although it does not directly impact the tones and subtle overtones of the acoustic guitar’s projection, the headstock is a place on the guitar where most luthiers display their logo, insignia or trademark.

With low end, budget guitars, this could be accomplished with a simple painted or printed laminate logo. With some more intermediately priced or professional line guitars, this could be a place where guitar makers display their creativity with elaborate abalone nacre or mother of pearl inlays. In fact, some people have carved their names in historical guitar making by their elaborate inlay artwork, using mother of pearl, wood, other precious materials and even plastics.

Guys like Harvey Leach, who started out with some elaborate banjo inlays, began experimenting with different shades of the same kinds of materials to create special shading effects and 3D appeal to guitar inlays – things that many other inlay artists weren’t doing, simply because the demand for more “museum-like” pieces came from high end guitar makers like Martin.

Another well-known inlay artist is Larry Robinson of Robinson Inlays, who did the exquisitely elaborate artwork on the “Millionth Martin.” He is even noted on writing THE book of inlay artistry, The Art of Inlay. And while the body of the acoustic guitar (notably the back and sides) is a great place for displaying their giftings, the headstock is usually the most common notable area for branding or “trademarking.” And, although the inlay industry was once a niche industry, it is beginning to gain more and more adept artists who are quite inventive and capable.

The function of the head

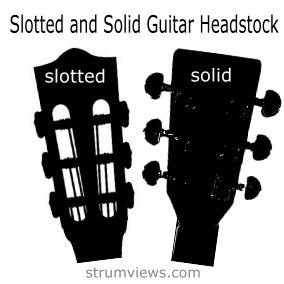

The headstock or head of the guitar is also to be home to the six tuning keys, also known as tuning heads or tuning machines are located. The strings are fastened and adjusted here at the headstock, opposite of the saddle and bridge on the body. Additionally, the headstock is usually carved or shaped from the same block of wood as the neck, being one uniform piece. Some common woods used for guitar headstock are Mahogany, Maple, Rosewood, Cedar and Walnut. With that being said, the tuning keys in the head can be made of many different kinds of metals and qualities, and they generally come suited for two kinds of guitar heads, slotted and solid.

The headstock or head of the guitar is also to be home to the six tuning keys, also known as tuning heads or tuning machines are located. The strings are fastened and adjusted here at the headstock, opposite of the saddle and bridge on the body. Additionally, the headstock is usually carved or shaped from the same block of wood as the neck, being one uniform piece. Some common woods used for guitar headstock are Mahogany, Maple, Rosewood, Cedar and Walnut. With that being said, the tuning keys in the head can be made of many different kinds of metals and qualities, and they generally come suited for two kinds of guitar heads, slotted and solid.

Slotted heads are very typical designs for classical and flamenco style guitars, whereas solid headstocks are more typical of your common steel string electric or acoustic guitar (though this is not always the case as some blues guitars and other steel string models use slotted heads in their designs.)

Of these two headstock designs, machine heads can be essentially open, where one can see the working gears and worm gears, or closed, where they are concealed in a chrome or other metallic housing.

The machine head (tuning machine or tuning key) is essential in maintaining the tuning of an individual string – six-string guitars have six tuning keys.

Each machine head consists of a capstan (post where the string attaches), the pinion gear, the worm gear and the tuning knob or key. The worm gear is essentially a screw that when turned at the tuning knob, it turns the pinion gear (or worm wheel) and the capstan, thereby tightening or loosening the string (raising the pitch or lowering the pitch). When looking to buy a guitar, it is wise to look for and test the quality of the machine heads. A quality machine head will be smooth and easy to tune, and will not slip from the tension of the strings or other environmental conditions.

The interesting physics behind the tuning machine allow it to be a “single direction” transmission. This does not mean it can only be turned in one direction, but that the direction of power transmission between gears works in only one direction. In other words, the worm gear is easily able to turn the pinion gear, but it is much more difficult for the pinion gear to turn the worm gear. This design allows the player to tune the guitar and put quite a bit of tension on the string without the string being able to turn the gears. If you want to test this, grab a string and try to pull the tuning machine around. You can’t do it. Some popular manufacturers of quality tuning machines are Gotoh, Schaller and Grover.

The interesting physics behind the tuning machine allow it to be a “single direction” transmission. This does not mean it can only be turned in one direction, but that the direction of power transmission between gears works in only one direction. In other words, the worm gear is easily able to turn the pinion gear, but it is much more difficult for the pinion gear to turn the worm gear. This design allows the player to tune the guitar and put quite a bit of tension on the string without the string being able to turn the gears. If you want to test this, grab a string and try to pull the tuning machine around. You can’t do it. Some popular manufacturers of quality tuning machines are Gotoh, Schaller and Grover.

Although this is not an exhaustive overview of the headstock of the acoustic guitar, it is certainly a good foundation and starting point depending on what guitar interests you may pursue. It is fascinating, however, to note how much of a mix of simplicity, beauty and complexity the acoustic guitar can offer, even in such a small region as the headstock. In another part of this series, we will take a closer look at the neck and fretboard, the amazing body (sound box) and an overall summary of some additional acoustic guitar terms and anatomy, including some good lingo to pack into your personal library.

About the author: Aaron Schulman is an avid acoustic guitar reviewer, teacher, advocate and family man. He enjoys studying and writing reviews about acoustic and acoustic electric guitars. One of his recent and favorite works is an in depth review of the Yamaha A3R with SRT Studio Response Technology.

Elliot (14 years ago)

This Guitar Anatomy series is a great resource for both new and old guitarists!

A decent Head-stock can make all the difference to a guitar.