By Michael Shea.

|

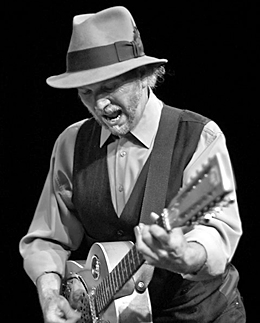

| Roy Rogers. Photo by Michael Shea. |

Let’s get it over with right at the start. Master slide guitarist, Roy Rogers, was named after the King of the Cowboys film star. Roy will be the first to admit that he’s had fun with his moniker. He named his record label Chops Not Chaps and he’s recorded his namesake’s theme song, “Happy Trails.”

“Pundits who bemoan the scarcity of guitar gods haven’t laid ears on Roy Rogers, whose slide riffs could peel a crawfish.” USA Today

Our Roy Rogers was born in 1950 and grew up in the San Francisco Bay area. He took up guitar at the age of 12, was turned on to the blues by his music teacher and soaked up the musical and cultural influences of the ’60s. Growing up in the Bay area provided stimulus not available in most parts of the country – diverse cultures, underground radio, and live music that featured prominent blues artists such as Muddy Waters, Albert King and B.B. King at San Francisco’s Fillmore and Avalon Ballrooms. It was a time and place with an explosion of musical innovation and interest in the blues tradition that radiated from San Francisco.

In the early 1980’s Roy spent several years touring with John Lee Hooker before going out on his own with The Delta Rhythm Kings in 1986. Since that time Roy has stayed busy, not only as a performer, songwriter, and recording and guest artist, but, also as a producer of recordings by John Lee Hooker and Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. Roy has been nominated for two Grammy Awards and three W.C. Handy Awards. He still tours the world with The Delta Rhythm Kings, alongside bandmates Steve Ehrmann (bass) and Billy Lee Lewis (drums).

Although Roy started playing slide after hearing blues pioneer Robert Johnson and toured with John Lee Hooker, it would be incorrect to pigeonhole him as a blues artist. True, he can play some great blues. But, his music goes well beyond the blues taking his slide guitar into new musical soundscapes.

A few days after he played to a sold out crowd at The Center for the Arts in nearby Grass Valley, Roy and I met at a small coffee shop to talk guitars and music in his hometown of Nevada City, California.

|

| Roy Rogers. Photo by Michael Shea. |

Roy Rogers: The show was fun the other night. I was very happy, delighted. We had a good turn out and, obviously, we had good coverage.

Michael Shea: You had great turn out. I go there often. I’ve never seen the place so packed. It was a great show.

Roy: It’s fun! The whole playing thing. You’re playing guitar and you want to get your licks out. But, it’s really about the energy. It really always boils down to that. And when I think back to when I first started, when I first saw guys that influenced me, Muddy Waters or John Lee, it’s the energy. It is not just the licks. It’s the energy that you put out. That’s really the key.

Michael: Talking about energy, if you’re playing a gig and everybody’s sitting on their butt and politely clapping, it would seem to me it wouldn’t really cut it for you. Does it?

Roy: It’s not as much fun. But, when you’ve been doing this a long time, you just address it differently. It’s not like it bums me out. You know what I mean?

You just play and it will put you in a different kind of mood to communicate. You won’t be rocking out and dancing around. But, you’ll be communicating in, maybe, more subtle ways. And that will affect my choice of songs.

I’ll change the set if I don’t see the crowd responding in a certain way. That’s a great thing about a trio and the guys that I’ve been playing with a long time. I’ll just change the set. But it’s not like it bums me out that they’re not getting up and rocking and yelling and stuff. That’s cool. I love that!

Like the other night. But, you know, the diversity is cool. I like the diversity. You’ve got a sit down listening crowd that’s intuitive. If you can use that word. I get more introspective.

Michael: That’s interesting, because when I go to a restaurant or bar and a guy’s playing and nobody’s listening, it seems like, “Man, I’d hate to be that musician.”

Roy: You know, I think it’s being honest. I remember playing a benefit for some club. I think it was the Sweetwater in Mill Valley. People were talking. Everyone was getting up doing some songs. And they asked me to come down and do a little short set. I started out playing with a lot of energy and then I wanted to play something more subtle, a ballad. Everybody was still talking and I just stopped and said, “You know, I really felt like doing a ballad and doing something soft. But, but if you don’t want to listen to that it’s okay with me. I’ll play something else.” And then everybody stopped and it quieted down with everybody hushing everybody. I didn’t do it for that purpose.

The best person I ever saw, bar none, with people talking in an audience like that was John Lee Hooker. It can happen to anybody. People were talking and he wanted to do something to get down, way down. He puts his hands down and says, “I want to get down.”

People were still talking. Well, he starts talking real low down like this. [Lowers his voice] He steps up to the mic and he’s talking like that. And nobody could hear what the hell he was saying! He had them quieted down. He didn’t try to overplay the crowd or play louder. Big mistake, don’t ever do that. He just got softer and softer. Finally, everybody perked up and said “What’s going on?” And the crowd was just quiet. Perfect. Perfect way to do it. No animosity. No weird energy kind of thing. You’re just doing your thing. But, you’re doing it in a way that’s a position of power. Isn’t it? It’s a way of control. It’s about the dynamics.

We’re going all over the map here. But I know with some younger bands that will open the show, they’ll come up and ask, “Hey, how does it sound, man?” In a lot of cases, upcoming bands will play at total volume from the first note to the last. It won’t vary until the last note. And I say, “You know guys, it was a real good set. The dynamics, where were they?”

The crowds can’t take it. If you have a conversation with somebody and you want to make a real big point you kind of go soft. Then you make a point and get loud. And I think that’s the key to communicating.

You gotta emphasize and then de-emphasize. And volume is crucial to that. You don’t want to blast somebody out. I tell people all the time when I go to sound checks, “You let me know about the sound out front.” My guy checks it. But, if we get too loud it’s going to interfere with communicating with the people. If they’re not worried about their doggone loudness, then it’s not helping me.

Michael: Is this something that you learned from just playing so long?

Roy: Dynamics you mean?

Michael: Yeah.

Roy: Oh sure, it just comes from playing. I’m 57 years old. I’ve been doing this all my life. So, you do it simply from playing in front of different crowds.

I’ve played in front of 100 people and I’ve played in front of 20,000 people. I mean, you have to address whatever situation you’re in. It’s not always going to be the same. But you have to be you. You don’t really change. You could be more dynamic. You can be more outgoing, if you will.

If you’re on a big stage obviously you’re not going to stay in a four-foot area. That’s not something that’s going to help you communicate to that crowd. You know, just obvious stuff. But, sure I’ve learned it over the years. I’ve played with a lot of people. I’ve played with Sammy Hagar and others.

Michael: He was on one of the songs on your Pleasure and Pain album. I really like that song.

|

| Pleasure And Pain |

Roy: Yeah, “Can’t Stop Now”. Well, Sammy’s a good friend of mine. When he first left Van Halen he wrote a song called “Little White Lie.” He asked me to play slide guitar on it. It’s really an interesting song because it’s acoustic and balls to the wall. It actually became a hit for him. I asked him, “Would you sing a song? I got this idea for Pleasure and Pain . I’d like to do a duet.”

I got him at the right time. He said, “You know that sounds like fun.” And I played him the song and he dug it. And I said, “Well, you know, vocally I can’t hold a candle to you Sammy. But, I think that this would be interesting to catch you in a situation that’s different for you. If it works for you, let’s do it.” We did it and it was really fun.

Michael: Great song.

Roy: It’s a fun song.

Michael: When I heard it I was thinking, is that Rod Stewart?

Roy: [Laughing] Don’t tell Sammy that!

Michael: I looked at your website. You have such a busy schedule. Have you had time to relax at home for a while?

|

| Roy Rogers. Photo by Michael Shea. |

Roy: I’ve really traveled a lot this year. I’m home now. We’ve been hitting it a lot this year. But I’m blessed. Knock on wood. It’s great now, you know? Let’s face it, I’ve been making my living at this for a long time. And it’s a tough business, as you well know. I’m lucky that I have all these places, a niche. My niche in various parts of the world. I go overseas a lot. It’s a big part of my performance. I consider myself fortunate. But, I do have to travel.

Michael: Does that get to be old for you?

Roy: It does. Just because travel has changed. Yeah, I long for the old days of travel. I’ll tell you, it’s not fun, especially with guitars. And you know the world is not the same. The time it takes to get through security blah, blah, blah. The flights, the airlines. Don’t get me started. Something needs to be addressed there. I missed every connection the last time I went to Europe because the flights were all delayed. Every one! Delayed me a day.

Michael: When you’re at home do you listen to music?

Roy:Oh sure.

Michael: Who do you listen to?

Roy: I’m all over the map. My tastes are really in a lot of directions. Everything from Erik Satie, a classical piano player, to Miles. I love Miles Davis! Probably pre-Headhunter days. I like early Miles.

Michael: The Kind of Blue album?

Roy: I’m a Kind of Blue guy. If I don’t listen to Kind of Blue once a month, I’m … it just puts me in that mood. It’s a very special record. It’s one of them. Ray Charles. Gotta listen to some Ray. It’s just certain people that put you in that spot. It’s a comfort zone for me and it’s about stretching music. When I listen to music it puts me in a comfort zone.

So I’ll go for flamenco. I like flamenco guys. I listen to a lot of jazz. And I’m big 78 collector. So I have a couple of jukes and I love hearing my 78s. I just love hearing them! You hear some Howlin’ Wolf on a 78 on a jukebox. He’ll lay you back! He’ll pin your ears back!

Michael: Do you play guitar when you’re at home?

Roy: Not too much. I’ll play guitar sometimes. But, not like daily. When you play so much on the road you get home and you do other stuff. I’m out cutting wood or something. Taking a walk on the trail. Like a lot of guys, I think I pick up the guitar and you never know where you’re going to go. I always like to keep a tape recorder or a pad and pencil handy. I find that you’re much more likely to come up with something off the cuff, just picking up the guitar and playing it as opposed to, “Oh, this is my writing day.” It doesn’t work like that. I’m sorry.

Michael: Do you tend to write the music first or the lyrics first?

Roy: Music usually comes first. Music defines the mood for me. I have done it the other way. But, I’m trying it the opposite, just to see how that works. You know, have lyrics, paint a picture and then see what comes up. Normally, the music defines the mood; sad, happy, pissed off, whatever. And then the lyrics follow that.

Michael: So, if you are angry and you get this angry music going, do you try to find some topic that makes you angry for the lyrics?

Roy: It usually comes to my mind. It comes out of the head like, “Wow! Use your imagination.” I could be in a bad situation somewhere. It’s whatever comes to mind. And it can be various things – nah, that doesn’t sound right. I wouldn’t do that. So I’ll just write them all down. I think it’s usually the first or second thing that comes off your head. That’s the key.

Michael: Do you have a favorite guitar for writing songs? Or a favorite key that you play in? A favorite tuning?

Roy: No, no. I have a number of guitars. I’ll play everything differently on a different guitar. Or, as you saw, I have a 12-string Dobro. That brings to mind a whole different palate. When I pick up my old National Steel a whole different set of ideas will come up. If I’m playing through one of my little amps and it’s completely fuzzed out and it’s like wacked tone, and you get the sustain, I want to do a chord and sustain for a minute.

Michael: Like the opening of “Bad Situation,” the song on your YouTube video? You’re playing a double-neck guitar and you’ve got this great feedback with the slide.

|

| Roy Rogers. Photo by Michael Shea. |

Roy: Yeah, I like to intro stuff like that. And it really depends on the guitar. You respond to what you hear. We’re all looking, at all times, for the tone. And, you know, that’s never ending. You have different amps and there’s no one guitar for me or one amp. I don’t have guitars necessarily for playing. It’s the tone. I didn’t really use both necks on a song the other night. It’s just got great tonality. It’s got the big P90s on it. It’s kind of small, but it’s got a big punch.

Michael: Are both the necks tuned the same?

Roy: No. One’s in G and one’s in D, so I can switch. And that was the whole idea. I very seldom play regular tuning on guitars. I’m always in open tunings with slide. But, upon occasion, I’ve had one neck to where I can play straight guitar, meaning regular tuning, and then switch to open.

But, most people, like rock guitarists that I’ve seen, not all, but most, if they’re playing slide in a rock band, they’ve got a rhythm guitar around. But if you’re doing both, playing rhythm and lead at the same time, like Delta style, which I’m derived from, then most guys are in open tuning.

Michael: The guitars that you used on stage, were they all in G and D or did you use some other tunings?

Roy: All over the map. The Martin was in E. The 12-string Dobro was in D. And the Strat was in G. And then the double neck was in G and D.

Michael: And you’ve got that little Les Paul Jr. up there too.

Roy: Yeah. I didn’t play that the other night. Sweet guitar. You know it’s a ’58 Les Paul Jr. and it’s got that great sound with that P90 and that big piece of mahogany wood. It just honks.

You know, for me it’s really the tone. Obviously you’ve got to be able to play it. But, my actions up a little bit anyway for the slide. Not a whole lot. But probably most guitar players that don’t play slide wouldn’t want to play my guitar. It’s up too high for them.

But the Martin, I would say, certainly is the main axe, because it’s got that certain balance. It’s a small bodied Martin, and I keep it, as you could tell, just on the edge of feedback. It’s just right. And if it’s the right set of circumstances, it’ll feedback. But it’s controllable. It doesn’t get away from me. A dreadnought style or a larger body would. Plus, it’s got that old DeArmond humbucker on it that just kicks ass. I wish I had a dozen of those. I only have about four of them. Can’t find them.

|

| Roy Rogers’ Stage Guitars. Photo by Michael Shea. |

|

| Roy Rogers’ Stage Amps. Photo by Michael Shea. |

Michael: When you’re out on the road , do you go to guitar shops and look for guitars, pickups or amps?

Roy: Oh sure! I’m always on the lookout. But, you know, those days are gone. Twenty-five years ago we could do that. Now all that stuff is gone. I’m always on the lookout for a humbucking pickup with the old tripod for an acoustic.

I have more guitar players come up to me upon hearing the Martin saying, “My guitar can’t sound like that. How do you make a guitar sound like that?” It’s the combination of the DeArmond pickup with the Martin, my Boogie amp and Leslie speaker.

Michael: Have you ever gotten rid of one of your guitars and later thought “Oh, man I wish I had that thing back!”?

Roy: Nah, the only guitar that I could think of, and it never felt right to me, was a Gibson 175. But it wasn’t an old one. And I got rid of it. I traded an amp once that I wish I still had. I had an old Fender Twin from ’63. But, I traded it for the body of a ’31 National.

I got the better end of that deal. I put a neck on it. It didn’t have a neck. But that National, I’ve got more studio work with that National. I mean, if you saw this guitar it looks like somebody just beat it on a railroad track.You know what I mean? We don’t want to know what went on with that guitar! It’s serious stuff. And it’s got this indentation in the bottom of the guitar like somebody flattened somebody. So, I always say somebody might have gone to blues heaven with that guitar!

I’ve got a fair amount of session work. I’ll bring that funky old ’31 National and then I have another National. It’s not new. It’s got more of a clean sound. I always pick the funky ones. Always. It’s just got so much character to it. That’s why the tone is so important.

I can’t emphasize enough, it’s the tone that really is the most important. I think I would take a guitar that was difficult to play with good tone, rather than the easy to play guitar with absolutely shitty tone.

Michael: Speaking of tone, when you record, or when you play small gigs or when you play large gigs, do you always use your same amp set up?

Roy: No, not when I record. When I record I have all kinds of amps. I set them all up. I have an old Valco. I have an old Epiphone from the early ’50s. I have a Princeton. I have my Boogie and have a Leslie. I have a big Leslie, little Leslie. I have a full palate when I record.

In records, you’ll always hear both electric and acoustic. I like the fullness of that, of both sounds. I’ll use different sounds. So you’ll get a real range of tones on the album. Generally that’s my set up that you saw the other night. I used to always bring a larger Leslie. It’s a motion sound Leslie. I don’t know if you’re familiar with that.

Michael: That’s with the rotating speaker?

Roy: Yeah. And then I’ll use a chorus pedal. That’s the only pedal I use. I usually always play off the breakup of the amp. Trying to drive the amp.

Michael: When you play a real large venue, how does that work since they have to mic the amp?

Roy: Always micing the amp. I mean on the extension speaker. I have a Bad Cat. It’s heavy to tote around. That’s a great amp. I love that amp! But, usually for my size gigs, it’s a little heavy to carry around.

I sat in with Bonne Raitt and plugged into her Bad Cat. Wow, what a cool amp! Bad Cat nailed it! You can’t have just a little distortion until you turn up the volume a certain amount. It’s just not there. Well, it’s cool from the word go. You have it. You don’t have to play it at loud volume. With the old Fenders you’d have to turn it up to like eight or ten, then you get your great tone. But you can’t always play at that volume. So, a lot of people have addressed this issue.

And my Boogie is a Mark II B from the late ’70s. It’s an older Boogie and it’s a great little amp. Just a great amp! It’s real warm. And I pull the gain boost out, so it gives me a little boost. It’s a real full tone. I want it to be full tone. It’s not too distorted, just enough. And it depends on the room. But, I like to keep it right on the edge. You might get this little whoop. But, it’s controllable at all times.

Michael: It seems kind of appropriate for your style of music too, to be right on the edge.

Roy: Well, it’s true. That’s a good point. Then you get into a whole philosophical thing about it. I mean, what are you trying to do? You know, I never had a hit record, per se. But, I’m known for a certain style. And I’ve been able to play all over the world and I play with a lot of people. And sat in on records so, you know, I can play, but for me, music is about stretching it. I could play Robert Johnson. But, why would I want to play something like Robert Johnson? I’ll play the song. But, I’m gonna play it like me.

You had Stevie Ray Vaughan covering Hendrix. I remember I did a tour with Stevie Ray before he died. He was doing these Hendrix things. And at first I was saying, “Why is he doing Hendrix stuff?” But then I got it. I mean he dug the song and he wanted to do it his way. It makes total sense if you’re moved by a song and you want to cover it. You’re not going to play it like it was originally, nor could you.

Michael: I love Albert King. Stevie would play some Albert King licks. But, he’d supercharge them. I liked that about him.

Roy: Yeah, coming at it from a different emotional perspective. And that’s a completely valid musical statement to do that. I’m not any kind of purest about music. To me it’s okay, I respect that. I’m not downing that. For me, it’s about stretching it. You know? The improvising.

Michael: I listened to the soundtracks from The Hot Spot that you did with Miles Davis. Slide guitar and trumpet sounds like such a weird combination but, man, it just blew me away. It really worked.

|

| Roy Rogers. Photo by Michael Shea. |

Roy: It really did. It still blows me away when I hear him kind of echoing slide. He overdubbed it after. We basically cut that live, except for Miles. Miles put his trumpet in and would echo certain statements of John Lee’s or my slide guitar. It’s just weird to hear him doing that. I get goose bumps just talking about it. It was a great session. And he really does the music. Miles and John had a great time and, of course, John and I had known each for some time. We were just in support. I mean, that whole session was, my understanding was, it was Dennis Hopper’s idea originally.

Michael:That combination of musicians?

Roy: Yeah. Because he knew Miles pretty well. John Lee was his favorite blues guy and he wanted to have jazz and blues for this real sleazy movie.

Michael: I was reading some reviews and people said the movie wasn’t that good. But, the soundtrack was wonderful.

Roy: We all had a great time. We had Earl Palmer on drums. The great Earl Palmer! He recorded with Fats Domino, early Fats Domino stuff from New Orleans. Lots of stuff he did in L.A. Tim Drummond on bass who played with James Brown. Great session! And Jack Nitzsche producing. Strange fellow there.

Michael: You grew up, basically, in Vallejo. This white kid from Vallejo hooks up and goes on tour with John Lee Hooker, the great black bluesman. How was that for you?

Roy: Well, when I first started playing guitar in 1962 my guitar teacher was Joe Wagner. Joe’s still around. He really put me in the blues as a young kid. I got in bands when I was 13. That’s 1963. That’s the book of playing Chuck Berry licks and Bo Diddley and all that stuff. But, he put me in a blues direction right off the bat.

Surf music was going on and Country and Western. Joe was a big fan of Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson and Freddie King, He showed me some of their riffs, in addition to the Chuck Berry stuff. He’s a great guitarist. I didn’t know who these guys were. I was a kid. My guitar teacher put me in that direction. And then I got in a band early on and then the whole British invasion came. I was a big Stones fan. And, of course, the Stones and Animals covered a lot of territory. I looked at McDaniel and asked, “Who the hell is that?” “That’s Bo Diddley.” “Who’s McKinley Morganfield? “Oh, that’s Muddy Waters.” “Who’s Chester Burnett?” “Oh, that’s Howlin’ Wolf.” I went on my own trek, you know? Remember, back in the ’60s it was wide open. And they had underground FM coming in. So we had the shift in radio. All these cats and underground FM!

So, I’m playing and I become immersed in blues. I was a teenager. And part of the immersion, not only playing in bands, was going to the Fillmore and the Avalon. I got to see Jimmie Reed and John Lee playing together at the Fillmore. And Muddy and Wolf and, you know, all these cats. I wasn’t really a big fan of the San Francisco psychedelic scene. Didn’t like it too much. I much preferred the emotional impact of the blues.

My older brother brought home a Robert Johnson record. That was it. I said “Wow, a slide guitar!” I was already a little rock ‘n’ roller playing high school dances and stuff. And then, through my twenties, the first record I ever made was with a harmonica player, a guy by the name of David Bergen playing around the Bay area. Playing the [Great American] Music Hall. Opening up for Taj, opening up the Keystone, all that stuff. We opened up for the Bobby Blue Band. It was a guitar and harmonica duet.

|

| Travellin’ Tracks |

Around that time I met Norton [Buffalo]. We didn’t play together. That’s when Norton had the Stampede. I formed a band in the late ’70s, probably ’79 or ’80. The style was just, “Where can I take slide guitar?” And that’s what really has evolved. And, of course, in ’82 I met John Lee through my bass player Steve Ehrmann and he put in a good word. I met John in Detroit on the first tour. He hired me. Before that I’d played a little bit with Luther Tucker. Do you know who Luther Tucker is?

Michael: Yeah, sure.

Roy: I played with Luther Tucker in the Bay Area. Used to rehearse at SIR on Folsom Street or whatever that street was, yeah, Folsom Street. So, I played with other people before. But, I very much felt in place with John Lee. I knew all his stuff and couldn’t believe I was playing with John Lee Hooker. I played with John from ’82 to ’86 and we became very, very good friends. Became very close to him and his family too. He was just one of the grand old men. I used to tell John, “All we can do is shine your shoes!”

Michael: So, now you’re doing a gig with Ray Manzarek. When you’re playing with someone, like a keyboard player, do you have to approach songs differently? Instead of being the front guy, do you find yourself hanging back?

Roy I’m hanging back. With Buffalo we’re both up front because we’re both kind of going at it. But, with Ray it’s a little different tour, because it’s more lyrical and we’re doing a very different range of material. It’s really about the guitar-piano duet and weaving that together.

But, yeah, I’ll hold it down in a different fashion with Ray and be much more chordal. I mean, I’ll play slide guitar but, less so. More guitar textures and then the weaving with the guitar-piano duet. So it’s very different. You’d have to hear it. It’s a little jazzier and more atmospheric.

Michael: How do you guys work out your arrangement?

Roy: Just by playing it. We just play it. We got together and rehearsed it a few times and said, “You know, this kind of feels pretty good.” Ray and I get along great. He’s a great guy. You know he still tours Riders of the Storm with Robbie Krieger. It’s a different facet of playing. And I like that. I’ve always kind of done different projects.

I’ve sat in with everybody from Jason Newsted and I did a project that you probably never heard of with the bass player from Metallica. Great player, great player. Jason and I met at a benefit for a kids at risk kind of thing. He was already gone from Metallica and we did a project together that we should put out sometime. It’s only a five song thing. Very different. I like that. Part of the excitement.

Michael: It must make it more interesting

Roy: Makes it interesting and I like playing with different players. I think there’s always something to learn. I remember being asked by somebody along the way, “Do you feel like you’ve accomplished what you wanted to accomplish?” Boy, if I ever feel like that, I’ll probably be dead. You should never feel that way.

Michael: That’s what’s so cool about music. There’s so much. There are so many styles. There are so many scales.

Roy: Always a different approach. It’s not like I’d go home and practice scales everyday. No, I don’t do that. But, it’s just exploring. It’s being open to new ideas with your instrument and other people, and listening. It could be listening for the first time to something that will really knock you off. It could be listening to something that you might have listened to a hundred times., But, now you hear it completely differently. That can happen. That does happen! Sure, it’s all there. That hasn’t changed. But, you change.

Michael: I imagine over the years that you’ve tried out many different types of slides. How did you decide on the one you use and what do you use now?

|

| Roy Rogers. Photo by Michael Shea. |

Roy: I like a couple of different slides. I’ve always used glass and steel. I used to use a real tiny one like Muddy Waters used. It was the inside of a faucet. And it had threads on one end. I used that for years when I was younger. But, it was a little thin. And I found that I like slides a little bit thicker for tone. Metal and glass are a completely different tone to me.

Metal’s a little more sharp. Glass a mellower tone. Just to my ear. I’ll use a thick glass slide. I think it’s a 212 Dunlop. Right now my metal slide is made by a friend of mine. His name is Tom Harrison. And he’s got this slide called a Texas [Blues] Tube. It’s electro polished. It’s not chrome. A low polish. Really got a nice feel, the inside and the outside. It’s made with a different way of the metal adhering to the pipe. And it just feels almost like glass. Very unique. Very expensive to do. So, I’m using the Texas Tube for a metal one. I don’t know if I used the metal the other night. It really depends. I’ll vary it. But, usually I’ll use both within a night.

At this point, I mainly use glass. But short, never big. Because you’re never going to use all the surface anyway. You mainly use the top portion. You’re not doing a six-string chord thing too much. I think Ry Cooder uses a pretty big slide. I don’t know about Sonny Landreth. It’s whatever your comfort zone is. For me, it’s short and thick.

Michael: I’ve seen Sonny Landreth a few times and it seems like a lot of his sound comes from his right hand. He’s damping and he’s doing all this stuff. How about you? You play totally different styles?

Roy: Yeah, we both love each other’s playing. We don’t run into each other too often. We just played at the Santa Cruz Blues Festival this past year. It was really great. I love Sonny’s playing! I don’t know exactly how he dampens his strings. I control it with the palm of my right hand. So, the cleanness, you don’t hear a lot of peripheral strings. You’ve got to dampen it. Just always up and down, up off the bridge.

Michael: You seem to go back and forth between finger picking and using a flat pick.

Roy: I started out with a flat pick. I’ll always use a flat pick. But, I like using fingers. So, for subtley or in combination, it’ll always be like that.

Michael: Since your fingers are so important to your career and your playing, if a buddy comes along and says “Hey, Roy, let’s go play some volleyball.” Do you say “Heck no, I don’t want to mess my fingers up.” Would you do anything special to protect them?

Roy: You know I try to. I’m real conscious of my hands. But, I’ll be out chopping wood up here and doing stuff like that. I always wear gloves, that kind of thing. Maybe not volleyball but, you know, I play a little golf. I like to play golf every once in a while. I’m certainly always conscious of fingers and hands. I mean this is how you make your living. I have fairly small hands, but, long fingers for my hands. Sure, I’m always conscious of doing stuff.

Michael: After playing for so many years, do you do anything special to protect your ears?

Roy: I’m more deaf in my left ear. My right ear I always plug. I don’t have ear monitors. I know a lot of people use them. But, basically I have a built-in muff in this ear. And it protects the ear, in a way. I have tinnitus. I don’t know anybody my age that doesn’t have tinnitus.

Michael: I have it too. Sitting here talking to you, I can hear it. I always hear a ring. I listen to so much live music that I now use some real high tech earplugs.

Roy: We should have started the earplugs 30 years ago. I have tinnitus like a lot of guys. And it’s just something you deal with. If I’m playing on a real loud gig, I’ve got plugs. I don’t necessarily have to wear a plug in my left ear because I’m already kind of deaf on that side anyway, so it doesn’t bother me. It’s something you’re conscious of. Let’s face it, you’re going to lose the highs when you get older anyway. It goes with the territory. Loud music, listening to it over the course of a lifetime, it’s going to take its toll.

Michael: Back in 1995 I saw Joe Satriani at the Fillmore and the next morning while sitting in a room, I heard this loud-pitched hum and thought, “Man, these fluorescent lights are really loud.” Later, I walked out of the room and still heard the hum. I realized I had finally done it.

Roy: I can remember an instance, playing at a club, this was many many years ago, because it always used to go away. I remember, your ears used to ring if you’d go to a loud show at the concert hall and then the next morning it’s fine. Well one day, I leaned down, somebody had a Ram speaker and it was like a clavinet and it went ‘dink’ and I was right in front of it. It didn’t go away after that.

Michael: How about your voice? I imagine you have to protect your voice also?

Roy: Voice, you know, I can’t over-sing. I mean, I like singing. I don’t have a great voice. Vocally, I wouldn’t say fragile. But, I have to be aware of overdoing it. Like I can’t scream anymore. That kind of stuff. And not imbibing too much. It’s everything in moderation. So, that helps protect your voice.

Michael: What other occupational hazards have you come across as a working musician?

Roy: Oh, you know, the classic one. We don’t have to deal with smoke in clubs now. I remember playing clubs in Europe years ago. You’re on an elevated stage, there’s no fan, and you can’t see the audience because the smoke is staying right where you are.

I remember distinctly playing clubs in the early nineties, late eighties, and the smoke would just be there. And, of course, you ran into it here before the smoke ordinances. So it was certainly an occupational hazard. The other hazards, the classic excesses, people drinking too much or drugging too much. That kind of stuff. At this stage of the game, people have made this decision in their lives or not. And they’re paying the price or not. For me, it’s always been about moderation with drinking and staying out too late. I’ve never had a problem with that. I’ve never had a problem either way.

It’s been about the music. It’s been about playing the music and that’s it for me. It’s not been about the partying or becoming famous. I mean, everybody would love to have a hit record. I produced a hit record for John Lee Hooker, co-wrote “The Healer” with John Lee and Carlos Santana.

Michael: Is it kind of like that label that Guitar Player magazine gave you about being one of the great unsung heroes? Being labeled as a blues guy, that kind of comes with the territory doesn’t it? Blues is not a mainstream thing.

|

| Roy Rogers. Photo by Michael Shea. |

Roy: It’s not a mainstream thing. And it never has been, really. It’s about what you want to do with music. And that really is central for me. I have a fine life doing what I’m doing. I get to play with a lot of people. I mean shoot, I had Allen Toussaint on my records. He’s a friend of mine. You have your niche. You know, the blues is popular in totally different parts of the world.

Of course, people are aware of my association with John Lee Hooker and my records. So, no, we haven’t sold millions of copies. I think it’s about having something to say. As long as you’ve got something to say and you can communicate that through whatever music you play, it’s absolutely important.

Anytime I would think that it’s not working, I might think about not doing it. You’ve got to have something to say. Like the other night, invite people in. It has to be a give and take. And you have to enjoy that. You have to be vulnerable, basically, to doing it. You have to say, “This is me.” I’ll play it with stories or however you do that.

Michael: Speaking of stories, could you repeat the story about playing “Shake Your Money Maker” in China. That just cracked me up.

Roy: Norton Buffalo and I were in China on this great cultural tour. We were part of a whole aggregation of people from all around the world. I mean, from all countries; Kazakhstan, Libya, Germany, Italy, Sweden, all these different acts. Some of them were very ethnic acts dressed in traditional costumes. Others were just contemporary, but all presenting music to the Chinese population from around the world. This was put on by the Ministry of Culture in China. They sponsored it. It was a fascinating and wonderful trip. The camaraderie of everyone from all these different places of the world. Politics didn’t matter. It was about presenting this aggregation of music and culture. I think it’s probably based on prefacing the Olympics.

|

| Live At The Sierra Nevada Brewery Big Room |

I think they did this ongoing. This was a few years ago. On this one particular gig we had gone to the Great Wall of China to sightsee and then had this gig outside of Beijing. Somewhere out in the country, outdoors, and we were all invited to do one song that particular night.

The MC’s came up to Norton and me and said, “So what’s the name of the song you’re going to do tonight”? We said, “Well, we’re going to do a song, a very classic American blues song and the title is “Shake Your Money Maker.” The MC’s are a young Chinese couple who spoke perfect English.

So, they get out and they’re speaking in Chinese to the audience and there’s about 10,000 or 15,000 people in this huge audience. And Zhi-Wei Huang, our friend from San Francisco who was responsible for us being on this tour, he cracks up and falls off his chair laughing. He’s laughing while they’re announcing it! We’re waiting to go on and I said, ” Zhi-Wei, what’s so funny”? He said, “Well, they didn’t quite get the translation right.” “Really?” He says “Yeah. They just announced “Shake Your Money Maker” as “Waive Your Money Printing Machine!” I laughed so hard I had to get my composure. I tell that story a lot. I mean, it’s just so good!

Michael: Have there been any really any big disappointments while you’re on tour or in your musical career?

Roy: Oh, sure. Let’s see. You look back now and they were just disappointments at something that didn’t happen, I suppose. What comes to mind? Oh, well, actually there’s a number of them. One when I was a kid. I was about 18 or 19 and the band I was in called the Four Way Stops out of Vallejo won the battle of the bands. And this cat came up to me and gave me all these Atlantic Records. I remember the records were, The Best of Sam and Dave, which had just come out, Aretha Franklin ’69, so it must have been 1969, wearing that green dress on the cover and then, maybe, Albert King or something.

Anyway, he gave me all these Atlantic Records and said, “You know, I work for Atlantic Records. I’d like to talk to you. I’m going to call you in a couple of weeks.” We just won this battle of the bands and I said, “Wow, that’s pretty cool.” He got fired in the next two weeks! So, that was kind of like a bummer.

And then what was the other one? I made a record for Liberty Nashville. This is a heartbreaker. The name of the record was “Slide of Hand.” It was with Jimmy Bowen, who was responsible for Garth Brook’s success. He was doing this whole Liberty Nashville label. I did two records that are now out as The Best of Two – Slide of Hand and Slide Zone. Well, he got in a beef with EMI right when my record came out. We cut a video to this tune, “Bad Situation.” They loved the record! They were really going to promote this record! This is a classic music business story. They spend a lot of money on it and I’d never made a video with a band before. Full tilt deal. And he snuffed the label. He said, “I’m done.” Right when the record came out! So, it was non-promoted. The A & R person that was my personal label left. Just like being thrown against the wall and dropped.

Michael: You hosted the Slide Guitar Summit at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival in 2005? What exactly was that?

|

| Roy Rogers. Photo by Michael Shea. |

Roy: I was asked to host the Slide Guitar Summit. We closed out the blues camps at Jazz Fest that year. And I had Lil’ Ed of the Blues Imperials, John Mooney, Bob Margolis, this other guy, I forget his name. Anyway, all these slide guitarists from in and around New Orleans and outside Chicago. It was billed as the Slide Guitar Extravaganza.

I just organized this thing and got the tunes to feature these guys at the Jazz Fest. It was a big, big success. Lot of people came. We were right up there with the major acts. It was fun just to facilitate people, backing them up, and performing. I enjoyed that. I love backing up people, because you only want to make them better. And then we had a competition at the end where you had four or five guys on stage. It was all cool.

Michael: It seems they might feed off of each other’s energy. Fire each other up?

Roy: Feed off each other’s energy. Organized it that way. I don’t normally jam. It’s gotta be in an organized fashion. Jams can be good. But, jams can be just bullshit.

And we try to stay away from the latter, because it has to be a situation where the music’s gonna be first, not personalities. So, that’s a crucial point and as long as people are approaching it as that, that’s okay. That was one of the situations that worked out just fantastically well.

You know, you’re always basically doing that on the fly in a situation where people are sitting in like that. We had the numbers and we gave them some choices of what songs. We had a little bit of a rehearsal, like a sound check kind of thing, but not much. You’ve got to read people. What’s going to make them comfortable and what’s not. People aren’t playing with their own bands. It’s always a little bit of, “Okay, is this gonna work or is this gonna not work?” And I’m happy to say it was a comfortable situation. Everybody felt great.

Michael: You’ve been playing with the Delta Rhythm King for many years. Do you ever feel like it’s just another day at the office?

Roy: I’m gonna give it up if I ever feel that way. The travel gets a little old, but not the playing. The playing is the easy part. Someone once said, I’ll give you a great Ray Charles’ quote. I believe it was when he was in Europe. This is second hand, so you can use it or not. Somebody asked Ray Charles about his career, and said, “You’ve had such a great career and you make a lot of money!” He said, “Uh, uh, I play for free.” And the interviewer said, “Wait a minute. Mr. Charles, you don’t play for free do you”? And he says, “Yah, yah, I play for free. They pay me for all that other shit.”

Michael: Tell me about the oral history recording of Ramblin’ Jack Elliott that you’re producing. Is this in the spirit of what Alan Lomax did?

Roy: I produced a couple of records for Jack, The Long Ride and Friends of Mine. I’ve been friends with Jack now for, oh boy, at least ten years. Maybe a little more. And the thing about Jack Elliott is that he’s truly a living legend. He is the link between Woody Guthrie and Bob Dylan. He was the last guy to hit the road with Woody Guthrie, when Woody was still traveling.

Jack didn’t write a lot of material. But, he’s got stories and he has inspired more people than you can think of. We’re talking across the water too. He was one of the first folkies, folk artist to go across to England. He made recordings in England in the mid-’50s. He’s got stories about meeting the Stones, not just people here. When he came back to Greenwich Village in the early ’60s he was already the old man. Dylan and Phil Ochs and all those guys, they were the new kids. He had already been there in the ’50s and late ’40s with Woody Guthrie.

He recorded prolifically throughout his career. I want to get the stories and his narratives because people need to hear them first hand. He’s got an incredible memory about things in general and his travels have taken him far and wide. He’s got stories about Sonny Terry and Brownie McGee, Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and on down through the Rolling Thunder Review and farther. And he’s inspired so many people. Johnny Cash loved Ramblin Jack Elliott!

I wish Johnny Cash was still living. He would certainly make a contribution to tell people what a guy Rambling Jack is. Those kinds of people are what I’m talking about. So, I’m in the process of doing this recording and I have him up to 1963. There’s a long way to go. We’ve done early stuff, we’ve done family stuff and I’ve got to get him back in the studio and do maybe a couple, two or three more sessions. We’ve already got, probably, a thousand hours worth. I’m gonna edit it and it’ll probably be two or three CDs. And you know, he keeps his guitar handy, so if he feels like going into song. It’s not about recording his songs. But, if it helps him tell the story, that’s what we do. It’s a very cool situation, very cool. And I hope to have some special guests make some comments.

You know, Wavy Gravy’s a dear friend of Jack. I can’t tell you enough good things about Jack Elliott. He’s just one of those people that I think a lot of younger people are not familiar with. How could they be? They’re not really familiar with his recordings. Anyway, that’s my latest project. I’m about ready to start writing for my new record that I hope will come out in the fall, maybe this year. I’m in no hurry. But, I’m sitting on this record with Ray Manzarek. It’s done. We may do a more blues oriented record. I’m the kind of guy that when it comes to projects, I kind of got to get in the mood. It’s got to strike me that now’s the time to do it. I’m fortunate that way. In the meantime, there’s lot of places to play.

Michael: In closing, do you have any advice for aspiring slide guitar players?

|

| Roy Rogers. Photo by Michael Shea. |

Roy: You’ve got to listen to what moves you. Listen to a wide range of music. Not just slide guitar. The Blind Willie Johnsons, the Robert Johnsons, Son House, those guys, because that’s were it all starts. The Charlie Pattons. But then listen to some other people. Listen to some Captain Beefheart, listen to some Miles, listen to some other kinds of music. It all goes into the pot to make up what you play.A lot of musicians, regardless of what instrument they play, were influenced by Louie Armstrong or horn players. You didn’t have to play horn to be influenced by what somebody’s putting down. I think that’s true of music. Don’t be afraid to go out of a genre.

I think today, even with the advent of the Internet, people have their druthers and they’re going to certain segments and not experiencing others. We were exposed, like we were discussing earlier, with early radio. As a young guy, even into my early twenties, I was exposed to a lot of music. You’ve got these new situations like XM and Sirius that’s kind of similar to the underground radio. They’re exposing people to music.

But I’d say to players, listen to it all. Then it’s all going to go into the pot and it’s all going to influence something. It’s all going to be good.

Related Links

Roy Rogers

Michael Shea, Crosscut Saw Photography