by Vince Lewis.

Here’s a classic Guitar International magazine interview with the legendary Larry Coryell published on October 4, 2007.

|

|

Larry Coryell |

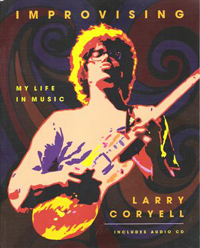

Larry Coryell has been, and continues to be, an innovative force of jazz guitar and is credited by many with being among the first players to champion the jazz-rock and fusion movements. After reviewing his new autobiography, Improvising: My Life in Music (Backbeat Books), I was asked by Guitar International to contact him and arrange an interview to discuss the book. The premise was to have one professional player talking to another about life experiences and music.

We spoke on May 29, 2007. I caught up with him while he was on the road to a weekend workshop he conducted at Jorma Kaukonen’s Fur Peace Ranch in Pomeroy, Ohio. A few seconds into the conversation I felt that I was talking to a friend of many years. The interview below is an honest and interesting representation of a fine musician and a true gentleman.

How does a high school pole vaulter end up a jazz guitarist?

Larry Coryell: I just couldn’t help it. I have no idea what caused it. It was just a natural flow of events. I was musical. I wasn’t aware that I was musical. It was just kind of in the shadows but it was always there.

Was your family musical?

Larry Coryell: My mother played piano and my biological father was a pianist, but I never knew him.

What caused you to become interested in jazz?

|

|

Larry Coryell |

Larry Coryell: The complexity and the mixes of the music and the fact that it was improvised are what really got me interested in it. Other music I could understand how it was possible to play, such as written music, but with jazz when I became aware that it was being made spontaneously, that was a big attraction.

When you were growing up did you play in cover bands like most of us?

Larry Coryell: Yep, exactly. Where I grew up it was pretty much country and western or as they say in Germany western and country.

You met Wes Montgomery in Seattle. What was your general impression of Wes? Was he easy to talk to? Was he forthcoming?

Larry Coryell: He was great! He was all those things. He was really a very humble man and because of his immense talent, he was thrust into the spotlight and he wasn’t really prepared. He was just a humble guy from Indianapolis. But he had that immense gift and he realized that even though he was nervous about making recordings and he never liked to fly that much, he made himself do it because it was part of his mission and his life. He was as friendly a man as you can get.

How much influence did Gabor Szabo have on you as a musician?

Larry Coryell: Very much, because he was bringing to the state of jazz guitar at the time a European perspective with his own particular quirks, like using open strings and borrowing some ideas that he had heard in Indian music. He was really bringing in different perspectives. He didn’t want to just sound like heroes as much as to do something more original. His influence is very big on everyone in that generation.

But, he was kind of on the fringe, one of the guys that didn’t get huge in the business.

Larry Coryell: He was big for a minute! He had that one album, Spellbinder, that was huge!

You were in New York during the mid-Sixties. Were most of the name jazz players accessible to newcomers at that time?

Larry Coryell: Yes, exactly that! Name jazz players were completely accessible in a very natural way.

You could just run into them in the clubs?

Larry Coryell: Absolutely!

When you first moved to New York were you playing jazz standards?

Larry Coryell: I was trying to get any gig I could get. I’d play everything. I played standards. I’d play music they’d play at Jewish weddings. I played a lot of blues. Anytime there was rock ‘n’ roll, that came easy. I also started playing the classical guitar at that time.

What attracted you to pianist Bill Evans and his music?

Larry Coryell: I think the same thing that everybody at the time was attracted by was his originality and his unbelievable talent and skill. He had carved out a style that was the polar opposite of the established Oscar Peterson approach that was very exciting and spectacular, and Bill Evans was more subtle.

I always think of Oscar as a hard driving guy and Bill with beautiful chord changes.

Larry Coryell: Yes, but Oscar Peterson did play “Waltz for Debbie.”

Oscar plays it and switches over to 4/4 in the middle.

Larry Coryell: Well, that’s actually in the arrangement that Bill wrote.

Tell us a little bit about Grant Green.

Larry Coryell: Just read the chapter. Everything about Grant Green is right in that chapter [Chapter 10: Okay, Coryell, dig Grant Green and you might just learn some music]. Walking into that club, there wasn’t even a bandstand. There was just a set-up at the end of the room. It’s still like that today in the world of jazz. Two nights ago we played in a place in Cleveland and it was just like that. We set up on one end of the room. There was no stage. But the guy promoting us made a great introduction and we got up there and we played like our lives depended on it. I learned that all those years back in 1965. That was a pivotal moment in my life when I actually saw Grant Green. I learned how much I needed to work on and how much I needed to work to become an artist.

The jazz business hasn’t changed a lot over the years has it?

Larry Coryell: It’s changed a lot in many ways. It’s become an industry. I don’t think it presented itself as an industry back in 1965. Especially with the extension of the business into Europe and Asia a lot of stuff has changed. But that aspect, what I’m saying about playing in a club, has stayed the same.

When you started playing with Gary Burton how did that change your personal approach?

Larry Coryell:It became more precise. Everything was more like being part of a finely engineered Swiss watch, an extremely modern and progressive avant-garde Swiss watch. There was a lot of controlling influences built into the concept which made for a very coherent group. I don’t need my bands like that. I don’t tell people how to play or what to play unless absolutely necessary. But, at that time that was what I needed and that was a good group.

Were the arrangements tremendously or tightly rehearsed?

Larry Coryell: Every time I couldn’t’ play the arrangement it was a real struggle to keep up. That’s how you get good, when your weaknesses are exposed. Out of professional responsibility you have to work on those areas that you’ve neglected up to that point.

|

|

Improvising: My Life in Music |

You state in the book that you wanted to blend the contemporary sounds of rock and pop with jazz, and you were one of the forerunners of that. Did you feel like the standards had been done to the point to where there wasn’t much more you could do with them?

Larry Coryell: Oh no, I didn’t feel that way at all. I just felt that this is what we had to do as our young group of musicians was coming on to the scene, that we had a responsibility to bring something new to the table, in addition to the standards.

That’s the feeling I got, because you continued to record standards.

Larry Coryell:Sure. Our job was kind of twice as hard because we wanted to learn from the masters and emulate them, but we felt the responsibility to bring something innovative to the table. So we had to kind of work twice as hard. Hard work never hurt anybody.

You were associated with producer Creed Taylor in the early ‘90s for a short period of time. Was his idea to get you better known to the public like Wes?

Larry Coryell: Well, there was only Wes, so I didn’t think it was the same thing. I really felt that Creed saw that I had abilities and that I had something special and what he did, and I allowed him to do, as a producer was to get me to water down my playing so that it would be more accessible to a wider audience.

I lived with that because I thought it was important to reach a wider audience, to get on the radio, to make some films. It’s just part of the business. But there was a moment when we were doing one of the last records where I realized that by following his direction I’d taken all the Larry Coryell out of Larry Coryell’s playing and I decided that I wasn’t going to do that anymore regardless of the economic consequences. It’s like asking you not to be you.

Do you look back and like some of the things you did with Creed Taylor?

Larry Coryell: I loved the digital duet with Wes [“(Angel on Sunset) Bumpin’ on Sunset” from Fallen Angel] and I loved that Brazilian record [Live From Bahia]. That was fantastic. And some of the stuff from the later records, the Peabo Bryson stuff [e.g., I’ll Be Over You]. That was really watered down, but we wanted to get on the radio. We wanted to get air play. It was tough to get on the radio if you were a jazz musician and Craig did it.

I talk about it in the book [Chapter 37: Coryell gets “commercial” – O, transgression, thy name is airplay!]. I mean you have to do it. But, I’ll tell you who does it better – Pat Metheny and George Benson. They play how they normally play and they get played on the stations. And Lee Ritenour too. They just have a natural way of playing that gets past program directors.

What generated the things you did with guitar and orchestra during the early ‘90s, and did you enjoy doing them?

Larry Coryell: Yes I did. I was offered a commission by some people in France first and then from some people in Italy. I was learning on the job. When I went back and performed the first concerto that I wrote for a second time, I’d made a lot of changes and I felt good about that. After the second time I performed it, I ended up coming right back to New York and played the whole thing on guitar and it was recorded by WNYC. I heard it played on the radio that’s on cable TV and I called up WNYC and asked if they could send me the DAT of it. They sent it to me and it was flawed. It would start playing and then something would drop out, so that recording is lost.

I’m very fond of what happened. I mean, it was really what I was trying to do initially in ’65, to keep the tradition that had come before us but try to put in something innovative as a responsibility of my generation.

Some modern players go “outside” so much that it’s difficult to justify. The things you do still have enough form.

Larry Coryell: Yeah, I know what you mean.

In your case, there’s never been a lack of form and direction to latch on to regardless of your listening background.

Larry Coryell: It’s easy if you you’re an advanced artist – you can play abstract and totally free, although I’m not sure it’s going to register in everybody’s ears.

Some modern players appreciate that as well.

Larry Coryell: Yeah, well, each generation produces its own people. We’re really a product of our times. Just like Abraham Lincoln was a product of his times and the Civil War, in ’65 there was also a war going on and people were demonstrating against it and African Americans were fighting for all the rights they should have had 100 years before. All of my heroes, or most of them, were black.

When I realized what a genius Wes Montgomery was, that was my breakthrough in understanding human nature. I realized that I was a white guy that didn’t know shit. It changed my whole perspective! [Laughs]

You’re on the road now?

Larry Coryell: I’m on the road now. But I was off for a long time. We wanted the time off because my beautiful wife of two weeks, Tracey, and I wanted to plan a wedding that was memorable and worthwhile. So, instead of going out and making money, I spent money on the wedding and it was good for all of us. We play Chicago, Ann Arbor and then I fly to Krakow, Poland, to do something with an orchestra.

Do you see yourself writing more method books and are you doing any teaching?

Larry Coryell: The Fur Peace Ranch is a teaching thing that we’re doing in Pomeroy, Ohio. I definitely see myself doing more teaching, if only to pass on maybe five or six things that I’ve learned that are so important in music that if they don’t get passed on they’ll be lost, and not just guitar artistic things. You know the old adage, “He who learns things the hard way never had enough sense to come out of the rain”?

You see, I got scolded by older musicians when I’d do things that were musically selfish and stupid and I try to pass how to avoid those mistakes on to the younger players in the spirit of “let me have done it for you” – let me have done that stupid mistake so you don’t have to. This is what you do in a particular section of a tune. You always do this and you never do that. It’s about giving structure to the improvisation so that it doesn’t sound completely abstract and free.

What prompted you to write your autobiography at this time?

Larry Coryell:I felt that I had a long enough career at this point to talk about the truth of how the music that I was involved with developed so that the story would not be lost historically. There are a lot of different ways fusion developed and evolved, and in many opinions degenerated, and I needed to document that there was some willpower in what we were doing. We did kind of make up our minds to do something different, but much of it was also simply a matter of course – we were a product of the times in which we lived.

What would you consider your pivotal CDs, those that deserve special attention?

Larry Coryell:Of mine? I don’t know. I made a lot of bad records. [Laughs] I’d say Spaces, and I’d also say the concert at the Royal Albert Hall with John McLaughlin and Paco DeLucia [DVD: Meeting of the Spirits]. It’s not a record, but I think that’s important because it was jazz people using flamenco ideas, among others, to create another way of improvising. And the excitement of that group was important.

I like the record Live in Chicago on High Note and the record Tricycles made around the very same time. I like Monk, Trane, Miles and Me on High Note and an acoustic record I made in Germany called Private Concert [1999, Acoustic Music Records]. Those would be the ones.

What do you think is the current state of jazz guitar?

Larry Coryell: Incredibly good! Bill Frisell, John Scofield, Pat Metheny, Kurt Rosenwinkel, Ben Monder, Russell Malone. I love Russell Malone. It’s great. I feel like the war caused that to happen. John Abercrombie and myself, we were trying to push the envelope. Just listen to Jim Hall and Pat Metheny on that duet record they did [Jim Hall & Pat Metheny, 1999, Telarc]. Pat’s the deviation and yet it’s compatible with the pure thing that Jim does.

Your advice to young jazz guitarists?

Larry Coryell:I hate to say this, but learn the business first before you get start getting totally immersed in being creative. In my experience, if you’re immersed in the creative life you don’t think about business. This is especially true since the business has completely changed due to the mistake they made when they made it possible to create a CD on a personal computer. If you know the business correctly you can still make a killing.

I guess it goes without saying that musicians make the worst businessmen.

|

|

Larry Coryell |

Larry Coryell: I don’t want to say I was the worst businessman because that would give me a certain distinction I don’t deserve. [Laughs] I’ve done okay. But, I never got into it for the money. I’d say that as long as you’re going to get into it, become an expert in contracts, promoting, marketing, learn how to make your own product and sell it and make all the products.

I think the Internet ruined everything, but since that’s the way it is, you’ve got to work with the way things are. You’re dealt a different hand nowadays. There were a lot more gigs when I was coming up. The studio gigs have dried out to a large degree because everyone’s a studio whiz now. Everybody knows how to use Pro Tools.

You can be mediocre and with Pro Tools make a perfect record in terms of technique. I don’t know if the feeling would come through. I talk about it in the book. I stopped editing my stuff so much when I realized that I’d better live with what I think are my mistakes. I went back to Miles Davis who would do some stuff that was pretty out there that some people might think was a mistake – and I hear it and think it’s pretty good.

What group will you have at Jorma Kaukonen’s Fur Peace Ranch?

Larry Coryell: Mark [Mark Egan, bass] and Paul [Paul Wertico, drums] and my wife Tracy. She’s going to sing. She’s great! She’s actually a rocker so she’s a little bit shy playing jazz. But we found some material that works really good. You know, music is music.

Are you giving workshops at the Ranch?

Larry Coryell:Mainly we’ll be teaching on Saturday night. We’re going to do the concert thing and we’re just gonna knock the walls out. Nothing more fun than sitting in the academic classroom, analyzing stuff and breaking stuff down into little fragments here and little fragments there and then going on stage and cutting loose and turning your mind off completely. When you’re teaching and learning our mind is working overtime and when you finally perform you can turn it off.

I really appreciate your time and the many years you’ve put in to the craft and the great music you’ve put out there for us to enjoy. I hope the generations that comes after us have it available to them, understand what it is and enjoy it.

Larry Coryell:Well, you and I want the same thing. Thank you!

About Vince Lewis

|

|

Vince Lewis |

Vince Lewis is a veteran performer, composer and recording artist who has appeared with countless major entertainers and jazz musicians. Since actively pursuing a solo career, he has achieved national acclaim and airplay, as well as outstanding critical reviews in numerous major jazz publications. He has been a Heritage Guitar Performing Artist since 1991, and is currently a featured artist on their website and in their printed catalog along with Kenny Burrell, Henry Johnson and Mimi Fox. His latest release is a trio project with drummer Phil Riddle and bassist Tom Hildreth titled Charlotte Swing – The Gift (Redstone Jazz). Guitar Player magazine describes his playing as “silky-smooth hollow-body jazz with fluid bebop lines, flawless technique, and a Wes approved tone that’s lively and bright.” In addition to his performance schedule, Vince serves as an Assistant Professor of Music at Liberty University in Lynchburg, Virginia.

Related Links

Fur Peace Ranch

Vince Lewis’ review of Improvising: My Life in Music by Larry Coryell