by Rick Landers

This vintage December 2, 2004 interview recalls artist, Paul Olsen’s early days hanging out with Clapton, Ringo Starr, Robin Trower and other heavies of rock royalty.

******

Rock illustrator, author, screenwriter and musician, Paul Olsen, pulls out the stops.

Paul talks about his personal experiences with such rock luminaries as Procol Harum, the Beatles, Robin Trower, Graham Bond, Ginger Baker, Eric Clapton, and a host of others.

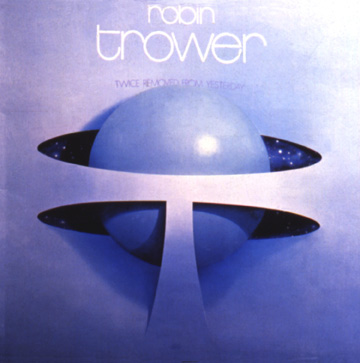

Many will recall those cool ’70s album covers of guitarist Robin Trower that Paul developed for the performer.

Twice Removed from Yesterday and Bridge of Sighs and In City Dreams, are some of Paul’s album covers that come to mind as album covers that captivated us before Trower’s songs were listened to on big head phones dialed to 11.

His books include: The Whole Enchilada, Airbrush, Dormouse, The Book of Love for Men, The Book of Love for Women and The Loop: A New Theory That Explains Why Things Happen the Way They Happen.

This early interview took place when Paul and Fender guitars were beginning a collaboration that would have produced an Olsen inspired grouping of Robin Trower album art on Stratocasters. In time, the collaboration proved unwieldy for reasons unknown, but the idea remains worth exploring.

Olsen and I still occasionally correspond and he’s still up to working up entrepreneurial ideas with guitars, music, restaurants and other workings of his spirited eclectic mind.

******

Rick Landers: Before we talk about the Robin Trower Stratocaster project, tell us about your background – where you grew up and the people who influenced you to become a free-spirited artist, musician, and author.

Rick Landers: Before we talk about the Robin Trower Stratocaster project, tell us about your background – where you grew up and the people who influenced you to become a free-spirited artist, musician, and author.

Paul Olsen: I was born in San Francisco and lived with my mother and father in the Haight Ashbury district for 1-1/2 years when they split up. I was then put in the care of my dad’s parents and lived with them out in the Sunset district of San Francisco.

This is especially poignant at this moment, because though I currently live in Studio City in LA, I am at a friend’s beautiful, restored Victorian in the City (all San Franciscans call San Francisco “The City”) having just traveled down from the gold rush country where my two sisters live and where our mother went into the hospital a month ago for major surgery and suffered complications for three horrid weeks afterwards that finally did her in last week.

We held a memorial for her three days ago that was a celebration of her life and had everybody both howling with laughter and suffering tears. Amazing woman.

I was basically brought up by my grandmother and her youngest son who had just returned from Army Air Force duty in the Pacific. Without him as a “father” I can’t imagine what a spoiled wreck I would have been if I’d only been brought up by my lovable Danish grandmother. She would have ruined me with kindness and misplaced “grandmotherlyness”. “Unk” was a terrific guy…a very principled man who taught me the right way to go about life. He set me on the right course and I am forever indebted to him.

Unk was so upset at the way the military did things in war – officers making stupid decisions that needlessly endangered lives – just like in Iraq today, that when he came home he swore he would never take an order from anyone ever again, and true to his word, he never did. Of course, because of this he never worked again, except of odd jobs for our neighbors. His example strongly influenced me to be my own man and really independent.

I pretty much stayed in the San Francisco area and ended up living with my Dad and his wife a couple of blocks from Golden Gate Park. My most favorite structure on the planet is still the Golden Gate Bridge.

Rick: Have you always been artistic or was there a particular turning point that led you into the world of art?

Paul Olsen: I was always “the artist” in school, from the fourth grade on, really. I’ve never had any formal training, only one brief night drawing course at Foothill College, but that was just so I could look at naked girls! Art was something that I was good at and when I was in high school I figured I’d either end up being an architect or a commercial artist. It just seemed a natural progression for the most part. Later, I ended up moving back in with my Mom and her two daughters in Foothill, what’s now called Silicon Valley.

Going to Foothill changed my life, because I met a guy named Bob Knickerbocker there, the most insane person I have ever met until I played with the great Graham Bond in England in the 70s.

I landed the plum gig of art director of the school’s slick new magazine, “Quasi”. Bob was the photographer and writer. We hit it off immediately. We were both interested in British sports cars, loved to race, and Bob, the bastard, actually had an MGA that we used to fly around in. Bob was the first truly artistic person I had met, in my protected, straight upbringing. He showed me there was an alternative way to look at the universe. This was 1961 – very early days.

We only lasted at Foothill a year. College was boring Well, okay, physics and chemistry were a pain in the ass and I hated them.

I wanted to get on with my artistic life and so did Bob. He headed back into the depths of Sunnyvale and I headed back north to the San Francisco. But Bob just didn’t head back into suburbia where he was from, he ended up in next-door Palo Alto with Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, Jack Kerouac, and his sidekick, Neil Cassady, unbeknownst to me.

I got a job as a production assistant at the giant Schmidt Lithograph company where I put my Quasi production experience to work. Schmidt printed labels – all sorts of labels, including the beautiful fruit box labels so collectible today

I was learning the trade from the production side of things at this amazing plant which not only made their own printing plates and coated their own paper but ground their own inks.

It wasn’t too long after that when Uncle Sam sent me an induction notice and I ended up with a Marine Reserve howitzer battery on Treasure Island in the middle of the Bay.

I’d been an Eagle Scout, so I figured the Marines would be a cakewalk. I couldn’t have been more wrong! Well, as it turned out, becoming a hard-ass Marine was one of the best things I could have done at the time. It makes you tough, fearless, and able to put up with anything life can throw at you, which, of course, is the whole point!

I was kept sane by letters from Knickerbocker with return addresses like “Why does it rain?” He really was my lifesaver and reminded me there was freedom and real life outside the confines of the Corps.

I then worked as an art director for a display company where I met an artist who had tried LSD and said I should experience this amazing drug. I had never taken an aspirin and don’t drink coffee, so I didn’t know what effects drugs could have on you, and certainly not dynamite like LSD. This was early 1965, very early days in San Francisco.

That experience changed everything. I saw clearly for the first time in my life, walked into work the next day, still stoned, no doubt, and told my boss what I thought of him and walked out, never to work for anyone else again until I painted the Starship Enterprise for the First Star trek movie working for Paramount Pictures. I guess I had quite a bit of “Unk” in me, after all.

Rick: Most artists can pick out an event or a piece of work that set them on the road to notoriety or fame. What was your “big break”?

Paul Olsen: I performed many street art events in San Francisco and became instantly famous when I changed a stop sign atop Nob Hill to read: “THIS STOP SIGN HAS TO GO!” That was at the top of one of San Francisco’s steepest hills and this stop sign was something everyone hated. The other three streets were dead level, and all had stop signs, so there was no reason for this one.

The picture was picked up by the wire services and flashed around the world. I was on the front the page of the San Francisco Chronicle the next day. I then formed the Psychedelic Raiders with Margo St. James, San Francisco’s most notorious madam, and we lit out at night and painted fire hydrants bright colors. The people loved them, the Department of Public Works hated them and painted them out every time they found one, causing quite a stir and protest.

It was then that I started doing firecracker paintings: glopping acrylic paint around a firecracker placed on a canvas, lighting the thing, and running away. The instructions on my Camel Brand firecrackers said: “Light fuse, run away.”

So that’s what I did! The resultant “paintings” were pretty neat, and I sold them all. I then had a show of 100 paintings that featured the original 1933 Monopoly board and one painting of each of the game properties, which sold for the amounts of money, in real dollars, that they are on the Monopoly board.

Rick: Your rock art posters are some of the most recognized artwork of the 1960s, how did you get become a member of the Funky Features crew?

Paul Olsen: I was living across town in 1965 and popped into the local used science fiction bookstore to find Yuri Toropov behind the counter. He had hair down the middle of his back. I had never seen a man with long hair before and was fascinated by him. We started talking, and he told me he was forming the Artist’s Liberation Front to give young, disenfranchised kids a chance to work with artists and learn various techniques.

The Front would hold street fairs all over town. A great idea, and I went to the first meeting of this group, where I met Bill Graham, who was managing the San Francisco Mime Troupe at the time, and also met Jack Leahy, who had a Triumph and an MGB. Leahy and I hit it off immediately and after the meeting raced across town to his flat where he told me of his plan to form a poster company with a friend of his, Sam Ridge.

Trouble was, neither of them knew fuck-all about posters, printing, or art! Jack had moxie, I’ll say that for him. I told him I knew all about the stuff they didn’t, and met Sam, and we formed Funky Features. I printed “Funky Sam,” “Funky Jack,” and “Funky Paul” on the cards as a joke, and the names stuck.

We rented a huge Edwardian house just off Haight Street in 1966 and started our business. I made the “Light My Fire” poster (see first image above) for a friend of ours who had money to pay me to do it (a novel concept!). We distributed it, and Funky Features was off and running. With the money from that, I did “A Day in the Life” and we sold thousands and began to build a business.

One day Jack put on an album he had just bought. It was Fresh Cream, which blew me away. When Cream came into town, Jack Leahy and I went to every concert at the Fillmore. I wanted to do what Ginger Baker was doing, and Jack wanted to do what Eric Clapton was doing (join the queue, Jack), so we traded artistic services with Don Wehr, at Don Wehr’s Music City, and knowing nothing about drums, I picked out a green sparkle double Slingerland kit I liked, with some help from Carlos Santana, who all but lived at the store at the time; and Jack picked up a Gibson SG with Sunn towers for amps and speakers (all JBL) in trade for doing a brochure for Don. I learned to play by listening to “Light My Fire” on headphones, and then progressed to Cream and Hendrix.

Cream – the moment I saw The Fool SG that Eric played on that first tour, I have wanted to paint a guitar for him.

I’m still waiting, Eric!

Rick : Who were some of the other poster artists?

Olsen: I met several of the Fillmore and Avalon poster artists, though I never did one of those posters myself, as I was too busy with my own company. We were all busy doing whatever it was we were doing. Besides, they didn’t pay – Bill [Graham] was paying $50 a pop, maybe $75 on a good day – not enough. My favorite of those artists are Rick Griffin, Victor Moscoso, Wes Wilson, and Stanley Mouse.

If you look at the first Fillmore and Avalon posters, they are quite “straight” in their design and presentation. Wes Wilson used the conventional artsy commercial west coast approach for those that was in favor at the time, but I think within a week or two, he must have taken acid, because almost immediately his whole approach changed. He hand-drew Alfred Roller’s turn-of-the-century typefaces and then expanded on them weekly so that within a matter of weeks, he had his own style completely.

See my website for the progression. It really is staggering, and demonstrates how quickly things were developing in the Haight because of the effect LSD had on everyone, especially creative minds. Rapid changes. But it was all Wes Wilson’s doing right at the get-go, and everyone else jumped on the bandwagon, though Von Dutch was doing wonderful stuff in LA on surfboards way before that, which is where Rick Griffin came from.

Rick: How did you first meet Robin Trower?

Paul Olsen: One night Sam was at the Club A-Go-Go in NYC and shared a table with some pasty-faced English guys in a band with a funny name who were just over on their first trip to America to promote their new single, “A Whiter Shade of Pale,” which we all loved. As they had no money and were driving across the country in a station wagon to gigs, Sam offered to put them up at our place, which they gratefully accepted, and we all became best friends and have remained so ever since. That’s how I met Robin and the band he was in – Procol Harum.

Procol would stay with us when they came to town, and when I moved to my own house, Gary Brooker and his wife Franky, would stay with me, which is where he wrote all the arrangements for the live album with the Stratford Symphony. Gary hired a concert grand for two weeks that filled half my living room and was fucking loud, while my huge drum kit filled the other half (and was just as loud), and we would jam all day long.

By 1969, things were turning sour in the Haight, and London was fairly zipping along, so I decided to abandon my beloved city and move to London. I had several friends there, including Procol Harum, and several pretty accommodating girls I knew. So I moved at the end of ’69 to a commune on Portobello Road, just a block up from where “Notting Hill” was eventually filmed

Rick: Something tells me there’s a story behind you getting the job illustrating Trower’s album covers.

Paul Olsen: Well, I met this delightful English girl named Lesley who showed me England and took all the rough, rude, American edges off me and showed me how to live a rich life with little money in my new country. And she taught me manners. English manners.

Six months after we met, we wanted our own flat and found one in Barnes, a village not that far away from Olympia or Notting Hill, but definitely a village atmosphere full of well-known actors and musicians. Around the corner were the famous Olympic Studios where the Stones recorded everything, and also where Cream recorded.

I was playing drums in various bands and trying to find a way to make money when one quiet Sunday morning in 1971, I walked around the corner to the news agents to get a copy of the Sunday Times and heard a raucous honking of a car horn behind me. I turned to see Robin and his manager, Ronnie Lyons waving and shouting, “What are you doing here!!??” They had recognized me from behind, and did not know I had moved to England! I leaned in the window and was about to ask Robin if he wanted me to do his album cover (it was obvious he was doing an album and I knew he had split from Procol) and before I could speak, Robin asked me if I would like to do his first cover for him! And that’s how I started doing Robin’s first series of album covers! It was meant to be. My life is like that.

Rick: Do you have a favorite Trower cover?

Paul Olsen: Definitely. My favorite cover, and in fact, the best painting I have ever done, is “Bridge of Sighs.” It’s great that it’s now a classic album too!

Chris Wright, of Chrysalis, owns the original painting and has it hanging in his London office. The original is so much better than the cover, especially the American one – they really cocked up the color separation. Nothing like the painting.

My favorite poster is my first one: “Light My Fire.” That’s one of my Funky Features partners, Funky Sam and his wife Jan. They have both since died.

Rick: What was your first Trower album cover and did Robin collaborate with you on the design?

Paul Olsen: The first cover was “Twice Removed From Yesterday,” and I went home after we ran into each other and said I’d meet Robin at the studio in about two hours and I started drawing thumbnails in pencil. I came up with a few ideas I liked and walked around the corner to Olympic and showed them to Robin. He picked one out and said, “That one.” I had no idea about what color so I asked him his favorite color. “Blue,” he said, and that was that.

All the other covers were done exactly the same way except I nailed down the colors ahead of time. I was supposed to do “Passion” and the live album, but record company fuckups prevented that from happening. I have the comps for them, though. The last two I did for Robin were another kettle of fish.

From Hollywood, I moved back to England in ’91 after finishing the Terminator 2 main title sequence. When Robin recorded 20th Century Blues in 1993, Derek Sutton, Robin’s manager, called me from Hollywood and said Robin wanted to see me. Robin lived just down the road from I was now living in Surrey, but that’s Robin – calling Derek way over in Hollywood to call me way over in England when Robin lived just up the road. This is when long distance calls were expensive and difficult to make!

I had painted some large canvases at my studio in LA in 1990 and brought them with me to England (they are now in a gallery in San Francisco, and if they don’t sell, back to England they will go with me when I move back next year!). I showed Robin some transparencies of my paintings just to show him what kind of thing I was currently into, to give him some ideas. After all, we hadn’t worked together for 15 years.

He picked one of the paintings and said, “I want that one.” I hadn’t meant for him to pick any of my paintings, but he knows what he likes, and when he makes a decision, that’s it. I thought I had done the painting from an album comp I did for my Aussie friend, Ron Charles, who had recorded the live Tommy album with Lou Reizner at Olympic in 1975, but when I got back and looked through my plan drawers for the comp and found it, I was flabbergasted to discover it wasn’t done for Ron at all, but as an alternate color comp for “Long Misty Days” which I never showed to Robin back in 1976 in Hollywood! I called Robin, and he laughed and said, “I guess I was really meant to have that cover, huh?”

I did that cover as my first piece of digital art on a Mac. The “Go My Way” cover was a digital image done where I now live in Studio City and was from a pencil drawing Robin sent Derek. That’s the first cover I have done with Robin from an idea of his.

Rick: Did you hear any of the albums before you came up with their art work?

Paul Olsen: I have never heard any of the albums before doing the covers, though I am familiar with Robin’s music and style, of course.

Paul Olsen: I have never heard any of the albums before doing the covers, though I am familiar with Robin’s music and style, of course.

I can’t say how I came up with the designs, they just appear in a kind of trance I get into as I draw thumbnails. It usually takes an hour or so (sometimes days) to “reach” that place where the ideas come from.

I have only just discovered, for instance, that the “Twice Removed From Yesterday” cover has a huge “T” as part of the design. A complete accident, or completely unconscious, but I never realized it until just a few months ago!

I’ve always loved symmetry, so anything I design is almost always symmetrical. The only cover that isn’t is the “Long Misty Days” cover. But symmetry, simplicity, dimension, dichotomy, and paradox are the things I like to incorporate into anything I do, so that determines to a large extent what I come up with in my designs. I like painting things that could be real, but aren’t.

Every design I come up with yields many more in the process so that now, even if I couldn’t come up with another design for the rest of my life, I’ve already come up with enough to keep me busy for thirty years. It’s a wonderful process, because it’s a geometric progression going the right direction. My only difficult decisions are which designs to use for a particular project.

Of course, sometimes a title will suggest a design, as did all of Robin’s album designs. The “In City Dreams” cover takes the slat motif of a park bench and turns it into a butterfly wing shape that can also be a freeway, so there is some dichotomy there. I threw in the chrome balls because I like chrome balls, no other reason, really. I also love Mt. Fuji, so I threw that in as well! That album really got the treatment, whereas the others are more stark, elegant, and mysterious. Not so defined.

Rick: In your journeys you’ve met a couple of the Beatles. Those must have been pretty exciting times.

Paul Olsen: Yeah, I’ve met two of the Beatles and played one song, with one.

My grandfather ran a restaurant in the Haight in the 1920s, and a family called the Shensons ran a deli nearby. Little Walter Shenson used to come into the restaurant and my grandmother befriended him. When I went to England in ’68 to print our posters, Gran said to look up now-big Walter Shenson.

Does that name ring a bell? Well, Walter Shenson produced the “A Hard Day’s Night” and “Help” movies. I gave Walter four copies of “A Day in the Life” for the Fab Four and he passed them on. He said I just missed meeting John Lennon who had been sitting in the still warm chair I now sat in. That’s the closest I came to meeting him.

I first met Ringo at Abbey Road Studios when I visited Gary and Franky at their flat in February of 1970. They lived a block away from Abbey Road, and Gary had just finished working on the album, All Things Must Pass, with George Harrison.

I first met Ringo at Abbey Road Studios when I visited Gary and Franky at their flat in February of 1970. They lived a block away from Abbey Road, and Gary had just finished working on the album, All Things Must Pass, with George Harrison.

Gary said, “Paul, I’ve got to nip round to Abbey Road to pick up some mics and cords, want to come?” Can you guess what I said? Of course I turned him down flat, it was too damned cold outside.

When we got to the studios, Gary said, “The Beatles studio is just down the hall on the right,” and I wandered down and into the control room. Here I was –where it all happened.

I was in a dream as I gazed down into the studio from the control room and thought of all that incredible music that had meant so much to me and millions of people all over the world that was recorded here.

I then noticed someone standing in the corner shadows. It was Ringo! I was wearing a large psychedelic button from Funky Sam’s collection, and Ringo was wearing a large “Sink the Magic Christian” button (the film he was in with Richard Burton). Ringo said, as I stood there gawking at him, “That’s a lovely button you’ve got there.” I quickly regrouped and rejoined with, “I’ll trade you!”, which we did.

Twenty-eight years later at Gary and Franky’s 30th anniversary party at a small village hall near where they live (where everyone had to wear the kind of thing they wore in 1968 – you should have seen Ringo and Bill Wyman!) I walked up to Ringo and flashed my Magic Christian button at him and said, “Remember this?” he looked at me quizzically for a beat and then said, “Abbey Road!”

I met Paul McCartney when drummer Denny Seiwell left Wings. I had been playing in the world’s first punk rock band, Third World War in 1971-2, years before the Sex Pistols, and we were on the Who’s record label, Track Records, which was run by a drummer named Jack McCulloch. Jack and I became friends and he introduced me to his guitar-playing brother, Jimmy, who had been gigging with John Mayall.

Jack called me one day and asked if I could share the drum duties with him and play with Jimmy at the Speakeasy, the musician’s nighttime hangout in London. I said, “Sure,” and showed up at the appointed time and we ran through some numbers.

Later that evening I got up and Jimmy and I blasted away (I can’t remember who was playing bass – it could have been Kim Gardner, but I’m not sure) when I noticed Paul and Linda McCartney in the audience. Jimmy was auditioning for Wings but he hadn’t told me, the swine. They had a good laugh over that one.

Jimmy got the gig with Wings, and in ’75, when Denny Siewell left, Paul rented the Albery Theatre in the West End for two days and auditioned 56 drummers including Phil Collins and Mitch Mitchell. Jimmy persuaded Paul to let me have a go, as he had already seen me play, and I showed up, nervous as a cat.

Paul was sitting in the stalls with Linda, and I spoke with her and then went backstage to warm up. Mitch was ahead of me and shaking. I couldn’t believe it. If he was nervous, what the hell did I have to be nervous about? So, when it was my go, I went out there, totally relaxed and played a number. I didn’t get the gig, but I was short-listed.

Then, in 1976, Wings did their famous “Wings Over America” tour and ended it in LA, where I was living, just above the Hollywood Bowl. I tried to get in the first of four nights at the Forum, but it was impossible. I was competing against movie stars.

I should have gone to the sound check in the afternoon, but I wasn’t thinking. They played four nights, and it was the event of the season, being covered in all the media, ending with a huge party at the Harold Lloyd mansion in Bel Air.

Everyone who was anyone in Hollywood was there, it must have been something. The day after the big party I got a call from Jimmy. “Where the fuck were you!?” he asked. I told him I had tried to get in backstage, blah-blah, and he said, “Paul, we expected you to come to the sound check. We rented a whole percussion setup for you – you could have played all four nights and gone to the party!”

Oof.

Jimmy was staying at John Mayall’s house in Laurel Canyon, so I spent two bacchanalian days there having a wonderful time.

That’s the last time I saw Jimmy – such a sweet soul. Strangely enough, George Harrison died just up the road from me in LA. I go by the house almost daily.

Rick: There has to be more you can tell us about your drummer career. Talk about your work with the great Jimmy Cliff, Graham Bond and others.

Paul Olsen: I already stated how I got my first kit. When I moved to London, I put an ad in the Melody Maker [the place for musicians to find each other at the time – Procol was partially formed that way] and formed a band called Jeep. We got a deal with a real sleazo publisher that wasn’t worth the paper it was written on.

I then played with various bands, filling in – there were so many gigs going on then, and it was all so easy to get work and to play. The perfect atmosphere for a musician and a golden era, really.

I auditioned for Third World War and played with them for a year until the manager ran out of money. I played for many of the Detroit soul bands that would pick me up as a drummer, saving the airfare of bringing one with them. I really enjoyed playing with Chairmen of the Board, especially. General Johnson had put together a great group of session musicians from Detroit, and my kick-ass style really shifted their tight, spiffy stuff sideways and the resultant music was great.

The best gig was the last one I ever played with them at the Kilburn State Theatre in north London. We had just finished a 20 gig tour of northern England and played top of the bill because of the single they had out, “Elmore James,” which was high on the British charts. When we got to the last gig, we were supporting Jimmy Cliff, who had the reggae hit, “The Harder They Come.”

At that time, reggae was in its infancy and just a bit sing-songy and not tight and spiffy like American blacks liked their music, and the Detroit guys poo-poohed it, having heard it for the first time on this tour. In the third number, we always stopped and just kept a bass and hi-hat drum thing going and General Johnson would take the mic and say how great it was to play in this lovely town, and we love England, etc. (they didn’t).

Well, this night we looked out on an audience for the first time that was totally black. Not a white face to be seen but yours truly. General Johnson, with his American POV, couldn’t help but say that as we have been touring the country we’ve been hearing a lot of this “reggae crap”. Well, the audience went instantly cold and we had to slog through the set with no response. When the curtain closed after the last song to no applause, General came up to me and asked, “What the hell happened out there?” I told him, and he said, “Let’s get the hell out of here,” and split.

I was undoing the cymbals and Jimmy Cliff came up to me and complimented me on my playing then said, “Uhh, I’ve got a little problem, mon. My drummer didn’t show.” Oh no. I knew what he was going to say and I told him there was no way I could play reggae because I had never played it and really hadn’t listened to it. Uh-uh. No. Can’t do. Nada.

Jimmy put his arm around me and said, “Come weeth me, mon” and led me downstairs to his dressing room where he lit up a Havana-sized splif and handed it to me (I don’t smoke anything, and certainly not dope) and I took a hit off this mother, then he handed me a bottle of 151 rum and tilted it up so I got a good swig (and I don’t drink spirits, either) and after my eyeballs stopped swirling in their sockets he smiled the biggest smile I have ever seen and said, “Now, mon, you can play de reggae!!!” That’s all I remember of the whole gig! I know it went well, because he asked me to join his band, but I knew I would be dead in a year if all their gigs ran on that chemical mix! I’ll never forget that gig, even though I can’t remember any of it. [smile]

I received a call from a bass player friend of mine who said he had a gig for me (we played well together) in a band that backed a new singer named Kiki Dee. The name didn’t excite me at all, I pictured some plastic blonde bimbo and wanted no part of it, but Phil insisted I come along. The rehearsal was the following day, so I agreed, what the hell.

I then received another phone call an hour later from Graham Bond, who wanted me to come to the country that night to play with his band – they would be up all night. I called Phil back and explained and said I would call in the morning. Graham Bond! Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce played with him for years before forming Cream with Eric! This was too good to be true. I felt a bit silly setting up my Ginger-clone kit in front of Graham, but we rocked all night and it was a perfect mix.

I joined the band and called Phil to turn down the Kiki Dee gig. Phil neglected to tell me that Kiki was Elton John’s protege and was getting first-class backing and had a single they knew would be a hit.

So, I played with the mighty Graham Bond – a kind of full circle from that first Cream gig 5 years before. We played some great gigs, the most memorable one at Dingwall’s Dancehall in Camden Lock, London. Graham moved in with Lesley and me and as he had no money and we couldn’t get a deal or gigs, everything dried up and no one wanted to touch him.

Then one day he went out for a walk and never came back. Three weeks later a policeman showed up with a greasy and bloody jacket Lesley had lovingly made for him – could I identify it? Yes, I could. Graham had fallen, been pushed, or jumped in front of an underground train at Finsbury Park station in north London. He and Oliver Reed, the actor, are the two biggest personalities I have ever met. Ollie was a wonderfully generous man.

I moved to L.A. in late ’75 and played with some English friends who had also moved there and met Charlotte Caffey at a gig one evening. She was forming the Go-Gos and we had a thing for about 8 lovely months, and then I played with several other friends and just before I moved back to England in 1991, I took lessons from Ginger Baker, who had moved to L.A., also.

During this time I was learning how to use an airbrush from the top illustrators in the country: Peter Lloyd, Ed Scarisbrick, Bob Hickson, and Charlie White. A call from Ed landed me the gig to paint the Starship Enterprise, and that led to special effects design and then main title design, culminating in Terminator 2.

Rick: I understand that Trower tends be something of a private, family man, but that you’ve had a bit of fun with him on occasion.

Paul Olsen: As I mentioned before, I met Robin and the Procol gang on their first tour, but didn’t get as close to Robin as I did with the rest of the band. Robin keeps himself to himself pretty much. You’re right, he saves all his sociability for his family – quite the family man.

The closest times I had with him were when he was living in California during the “In City Dreams” cover and the following live album, which I ended up not doing. While I was working on “In City Dreams” in my little apartment above the Hollywood Bowl, I got a call from Chrysalis saying Robin wanted to see how the art was coming along and would send for it tomorrow. Robin was staying at the fabulous Hotel del Coronado in San Diego.

The following day there was a knock at the door and I opened it, expecting a courier, but was faced with a limo driver who said, “Mr. Olsen?” I nodded and he said I was to bring the art and to come with him. I smiled. Robin was really laying on the red carpet treatment! What a luxurious drive to San Diego!

I grabbed the art and got in the huge car that nearly took up the whole driveway. Instead of going to San Diego, the limo driver dropped me off at LAX and handed me a first class ticket to San Diego! I flew down to be met by another limo that took me to Robin’s hotel. When I knocked on his door, he threw it wide open with a huge smile on his face. “Have a nice trip?” he quipped, and laughed. “I’m going to have walk back, huh?” I rejoined. Robin said, “Paul! You ruined my surprise!” Andrea, Robin’s wife was there, and we had a great afternoon together.

The other time was when Robin rented a house in the exclusive Malibu Colony, where I spent a few days with him and his lovely family. We drove his Corvette out to the sand dunes in Death Valley for a photo shoot for the live album. I’ve got some great pictures of him standing in the dunes with my large chrome gazing ball – too bad they were never used.

On the way back, we stopped into the hotel bar in Stovepipe Wells and had a beer. The bartender was quite excited as Marlon Brando was staying at the hotel. Robin asked him if he liked rock music and the bartender said, “Yes,” but Robin didn’t pursue it. Maybe he felt a bit out gunned by Brando — who wouldn’t?

We then got back into Robin’s ‘Vette. Both of us like to drive fast and we’re both good drivers – I used to race, and Robin raced all his Jags back in England. There was no moon, so it was dark. I’m talking pitch black.

I took the first leg and tore off up the long grade from Stovepipe Wells when Robin reached over and flicked off the headlights! I couldn’t see a damned thing and we were doing over 100 mph! I quickly fumbled for the switch as Robin laughed his ass off. Amazing we didn’t end up in a pile of fiberglass!

I also spent time with him and the family in England when they lived in Forest Row, right next to the famous 100 acre Wood of Pooh. We trudged around the Wood in the rain and muck and had a great time – even played Pooh sticks on that very same bridge.

Rick: Have you made any album or CD covers for any other artists?

Paul Olsen: I hoped there would be a lot more, but I haven’t done too many covers. The ones I did paid extremely well (much better than now) and kept my English girlfriend, Lesley and I going for quite some time. I think because Robin liked the first one, I got the call for the next one. Besides, I was good friends with everyone at Chrysalis, especially Chris Wright and Terry Ellis, the owners (hence the clever name: Chris-Ellis). Those were great days in England in the early 70s, the perfect time to be there if you were in the music business. I treasure my time there for that magical period.

I didn’t have a lot of time to do more covers either, because I got busy in the movie industry designing movie titles, and also doing a lot of hot rod magazine chrome lettering, which was fun, something I was good at and enjoyed, and that paid well.

I liked almost all the people I worked with on album covers. I did a cover for Hall and Oates, The Hoodoo Rhythm Devils, one for a guy in Chicago, and one for my friend, Saiichi Sugiyama who has just released his second album. Now I’m doing a lot of writing and directing, and that takes up all my time for the present, though it will all change when I move back to England next year and start a business where I get to play a cowboy! Yipee-ki-yi-yaayy!

Rick: How did the Robin Trower guitar project come about?

Paul Olsen: This is an interesting one. I got an email from Michael Indelicato (don’t you just love his surname?), a well-known vintage guitar collector and total Trower fan. Michael got into guitar collecting when he bought Robin’s first album because of my artwork, not knowing at all who Robin was.

Paul Olsen: This is an interesting one. I got an email from Michael Indelicato (don’t you just love his surname?), a well-known vintage guitar collector and total Trower fan. Michael got into guitar collecting when he bought Robin’s first album because of my artwork, not knowing at all who Robin was.

Since he now had the album he thought he would play it to see what was on it, and was blown away by Robin’s music and playing. And as I did when I saw Cream, Michael went out and bought a new Strat and learned to play and began to read everything he could on Robin. Robin said in one interview that his favorite Strat was a 1956, so Michael went out to try to find a ’56 Strat. He couldn’t find one, but he found a neat ’57 and bought that. And that started him collecting guitars.

Michael has always been into fine art and has quite a nice collection of paintings and wanted to know if I had the “Twice Removed From Yesterday” original art, because he wanted to buy it. I wrote back and told him that I had given it to Lesley after I did it, and that she and her husband had it above their bed in their big house in London and I’m sure she wouldn’t want to sell it.

He then asked me about “Bridge of Sighs,” and I told him Chris Wright had that and I knew he wouldn’t let that one go. Then Michael asked if I had any other Trower art, and I told him I had the color comps for “Bridge” and “For Earth Below.” Michael asked me to bring them up to his fancy house in Tiburon, and I drove up from LA and he took me out to dinner and then we haggled over the drawings, which I didn’t want to sell, but told him I had other stuff I would part with for the right price.

Michael wanted the two color comps and I said, “Michael, they aren’t for sale!” He laughed and said, “Paul, everything is for sale.” I shook my head and said, “OK, ten thousand dollars, and they’re yours, alright?” Michael stepped back and then said, “You’re right, they aren’t for sale, are they?” I laughed and said, “Right. Not for sale.”

Michael knew that I loved Triumphs and had once owned a 1966 Bonneville – my favorite motorcycle of all time. He said, “Paul, come downstairs, I want to show you something I think you’ll like.”

Down in his basement room were two mint English bikes – one a BSA Lightning, and the other a brand new, never been kicked over, 1966 Triumph Bonneville! How could this be? Michael told me the story.

There is a superb English bike restorer in British Columbia who was on a parts finding trip in New Zealand and came across a 1966 frame and engine (matching serial numbers) still in the factory crate in someone’s garage. They hadn’t been touched since they were made in England in 1966. He bought the unit, and then built a 1966 bike around it, using all 1966 brand new parts, all of which he was able to score. Michael ended up with this amazing machine as part of a trade.

I looked at him quizzically, and he said, “Sure, sit on it!” I got on the bike and all my memories of Haight Ashbury came flooding back sitting on the lovely machine with its wide handlebars and very particular seating position. No other bike feels like a Triumph. It was perfect. 0 miles on the odometer, all the decals in place – perfect. What a gem. I got off the bike and Michael smiled at me. He’s got a very charming smile when he wants to get something, and he said, “I’ll trade you the bike for the comps.”

I was struck dumb, then smiled and said, “You son-of-a-bitch!” and laughed. He knew he had me, the swine. We shook hands, and our friendship really blossomed from there.

Michael later opened E Guitars, a vintage guitar shop in San Rafael, just opposite Bananas-at-Large, as he had just purchased the famous Scott Chinery Guitar Collection, and had become friends with Alan Rosen, who manages Bananas-At-Large.

I met Alan and we talked about a project of Michael’s where we are going to put huge bronze stars in the pavement, ala Hollywood Blvd., and call it the “Legends of Rock” with stars dedicated to all the musicians who contributed to the music scene in the Bay Area. I would design the thing, and Archie Held, the famous sculptor who lived in San Rafael, would make them. Then Michael got the idea for me to paint one Strat with each of the seven covers I did for Robin, plus one compilation Strat, and I threw in the Star Trek Strat, and Alan ordered them from the Custom Shop and will sell them, and that’s how that happened!

Rick: Are you going to paint the guitars in the same sequence as when the albums came out?

Paul Olsen: Interesting question. I haven’t thought about it, really. Yes, I probably will. It makes a certain kind of sense.

Rick: Have you ever painted a guitar before? Do you anticipate any particular or interesting challenges?

Paul Olsen: I’ve painted only one, and that was back in 1969 for my friend, John Rewind. He had a Gibson 335 and wanted to call it “American Pickle,” with a pickle on each “ear.”

Paul Olsen: I’ve painted only one, and that was back in 1969 for my friend, John Rewind. He had a Gibson 335 and wanted to call it “American Pickle,” with a pickle on each “ear.”

I painted it with roses all over it, front and back, plus the pickles and it looked terrific. Trouble was, it got stolen just a year later and has never turned up.

I am really looking forward to painting the guitars. They will all be airbrushed and should be fun to do. The only tricky bit will be painting onto the pick guards – spraying over a frisket (stencil) that has to go across an elevation change will be tricky because the airbrush will overspray there. I’ll have to use automotive paint tape – it will be fussy, but should work OK.

Rick: Will the Stratocasters be Robin Trower Signature models?

Paul Olsen: I think they are the Trower Tribute series – all hand built, anyway. We are expecting them sometime in November, but Fender have still have not given us a firm date for delivery. Fender’s swamped with hand-built orders at the moment because of the 50th anniversary of the Strat. I will paint them at Archie Held’s giant studio in Richmond, just over the Richmond-San Rafael bridge.

Rick: Are the guitars going to be for sale to the public?

Paul Olsen: Yes! Through Bananas-at-Large for $9,999 each. I think someone at the Custom Shop already wants one of them, but I won’t say which one. But they are still all available as of this writing! They are for advance sale now, so if anyone out there wants one, I would put in my order, because there will only ever be one of each, and that’s it – they will appreciate in value. And, I think they will look pretty good. I’ll give them everything I’ve got.

Rick: Do you have any plans to paint guitars in designs like your poster art?

Paul Olsen: No plans for that. If someone wants me to paint a guitar for them, I will be happy to paint what they want as long as the price is right. If somebody wants me to paint one of my poster images or anything else of mine, except the Trower covers, then I will be happy to do it, but I could only do that before the Trower project guitars arrive or immediately after. I’m headed for England to raise some cash for my new business venture over there. Once I’m in London, I’ll be very busy for several years and won’t have time to paint anything!

Rick: We look forward to joining you when you paint the Robin Trower Album Strats.

Olsen: Thank you. I’m looking forward to getting those guitars and making them stunning, not that they aren’t already stunning pieces of hand-built Custom Shop craftsmanship!

|

Bridge of Sighs

|

||

|

Bridge of Sighs

|

|

|

|

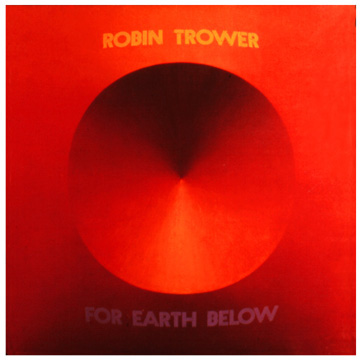

For Earth Below |

||

|

For Earth Below

|

|

|

|

In City Dreams

|

||

|

In City Dreams

|

|

|

|

Twice Removed from Yesterday

|

||

|

Twice Removed from Yesterday

|

|

|

|

20th Century Blues

|

||

|

20th Century Blues

|

|

|

|

Go My Way

|

||

|

Go My Way

|

|

|

|

Long Misty Days

|

||

|

Long Misty Days

|

|

|

|

Compilation

|

||

|

Contact Information

Paul Olsen

Website: www.olsenart.com

Book: The Book of Love