Editor’s Note: As Guitar International continues to migrate our past interviews to GI, we are pleased to present an in-depth interview with Fender Custom Shop co-founder, John Page, and owner of John Page Guitars, initially published January 27, 2007.

By: Tom Watson with introduction by Tom Wheeler and Pamelina H.

John Page with new Page P-1 (photo courtesy of John Page)

John Page is an artist, and he has had an appropriately romantic artist’s life. He was a rebellious preacher’s kid, runaway, Pup ‘n’ Taco worker, and oil field janitor who discovered Elvis and the Beatles and was transformed by rock and roll. He has practiced several forms of art, with formal training in none of them. He started his first band at 14, right around the time he built his first guitar.

This surfer/songwriter from the buttoned-down town of Whittier, California may seem like a dubious candidate for a leadership role of enormous responsibility at a big international company, but when you consider the company is Fender guitars, it all begins to fall into place.

John Page started working at Fender in 1978, designing and building guitars alongside the great Freddie Tavares, perhaps the most admired and loved of all the first-generation Fender employees. Freddie treated him like a son.

In 1985 William Schultz rescued a declining Fender from its corporate parent, CBS. As I wrote in The Stratocaster Chronicles, “[Schultz] recognized that even restoring the quality of the mainstream guitars might not be enough to salvage his troubled company.

Besides, he never liked the ‘working man’s guitar’ idea; it was fine as far as it went, but it was too limiting. Schultz imagined a new kind of Fender guitar, a new kind of Fender company. He told videographer Dennis Baxter: ‘It’s a working man’s guitar, yes, but Fender is more than that. People laughed when I said I’m gonna open a custom shop, but a Fender is a top-of-the-line product. It can be used anywhere. It can be a collectible. It can be used with a top artist. There’s no limit as to where we can go with quality and playability.’”

Bill Schultz tapped John Page to head the new enterprise. Under Page’s direction, the Custom Shop quickly established itself as Fender’s dream factory, a place where guitar gods and ordinary players alike could see the guitars of their imaginations made real. For a long time, accounts of the shop invariably cited examples of exotic one-offs — a Strat with two necks, or a Tele with a Strat tremolo, or some other never-before-seen 6-string mix-and-match concoction.

These stunners served their purpose. They delighted customers, grabbed the spotlight for Fender, and let people know that Fender was not only wriggling out from under the staggering stigma of CBS but was also on its way to reclaiming its lost reputation as the coolest house on Guitar Planet.

All well and good, but in fact the greatest significance of the Custom Shop lies elsewhere, beyond the notoriety and flash of producing one jaw-dropper at a time. John Page and his colleagues pioneered a long list of techniques and processes that would filter down to the production of Fender’s stock catalog models. You don’t have to buy a Relic or a Closet Classic or a Time Machine guitar to benefit from the hard work and brilliance of John Page and his colleagues and successors at the Custom Shop. Just walk into your music store and buy practically any recent-issue American made Fender.

— Tom Wheeler

I’m more of a believer in coincidence than destiny, but maybe there was a little of both involved at Winter NAMM in 1988. That’s where John Page and I met for the first time. The Fender Custom Shop was new and I was new to painting guitars. John immediately got me involved in working with the Custom Shop and for that I am eternally grateful.

John has the soul of an artist with great vision. He always strives for excellence and has the wonderful ability of inspiring the same in everyone he works with. The projects that he and I worked on together are some of my most proudest achievements. But what I’m most proud of is that after 20 years of knowing him, I consider him one of my closest friends.

******

Life before Fender…

John Page in 1974 (photo courtesy of John Page)

John Page: I was born in Inglewood, California, on May 9, 1957. I grew up in Southern California at a time when rock ‘n’ roll and the surf culture were also “young”, two things that greatly influenced my life.

I lived in Whittier. It was a small town that was originally settled by Quakers, a very conservative religious sect. I remember as a kid, driving by the old Quaker church and seeing them showing up in their horse-drawn carriages.

I know I’m not that old, but that was freakin’ weird. Anyway, growing up in the ’50s and ’60s, things were still kind of open in So Cal. We actually could walk to the market [about three miles away] through open fields. I really liked that, but it didn’t last too long. Southern California was booming.

My family was pretty whacked. It was the era of Ozzie and Harriet Nelson, but my parents made them look like Ozzy and Sharon Osbourne.

My dad worked nights as a printer so he could be a preacher and church elder in a very conservative religion during the day. My mother was a preacher’s wife and everything that you think that implies, does. I had to be the freakin’ “example” in whatever I did, from the way I spoke to the way I dressed and cut my hair, not to mention what I was allowed to do. So, I knew pretty early on in my life that things were going to have to change.

In the meantime, I had to do the shit I was supposed to so I gave sermons starting at a really young age and “preached the gospel” to all those damn unbelievers [Laughs]. I had my releases though. My parents called it “devil music” – yes, that’s right, rock ‘n’ roll. I was totally into Elvis as a kid.

I remember driving across country with my parents, it was 1963 I think, in this old ’54 Chrysler. It had really wide chrome trim on the backseat windows, so I used them like mirrors. I still remember being so bored that I kept trying to get my mouth to move like Elvis’ when he sang, I wanted to be just like him. Then the British shit hit the fan with the Beatles. That was it. After seeing those groups on Ed Sullivan I knew that that’s what I wanted to do – be a musician. That had to wait, at least for a while.

I started working full-time at the age of 14 as a janitor in the oil fields. I surfed with my friends every chance I got, started designing and making jewelry and even made my first electric guitar. My friends and I put our first band together, called UNILUV, one united universal love…yeah, I know, but hey, it was the ‘60s.

Of course, I was still a preacher’s kid, so I kind of kept the music quiet, until I was 17. That’s when I realized that life was full of options, so I bailed. I ran away from home, quit school and said “fuck the world”. That lasted until the place I was living for free booted me out and I moved back home. I stayed at home until I turned 18 and then moved out and got my own place.

What led you to music?

John Page and Paul McCartney – photo courtesy of John Page

John Page: Why did I take up music? Simple: to get my feelings out and to get the women! With the religious household I was raised in, I had lots of pent up feelings inside. Music, primarily songwriting, let me get all that crap out of me.

My first instrument was the cello, in the fifth grade. In fact, it was the only music training I ever had. I forgot it all the next summer. Anyway, I started writing songs when I was about 12. I didn’t play guitar yet, I think I started playing guitar the next year, at 13.

My dad had this cheapy classical guitar he bought in Mexico. He let me have it and I started dinking around. My buddies and I started our first band at 14. We pretty much just played for friends’ parties and stuff. It was kind of folksy stuff.

By the time we were in high school, we had gotten pretty good and had hooked up with some other good musicians. I never got that good on the guitar, but I had a really good voice, so I was the singer and rhythm guitar player and I kept writing a lot of our material.

By the time I was 17, I really thought I could make it as a professional singer-songwriter. I recorded my first demo the next year and hit the streets trying to place it with producers and get a record deal. I did all the songwriter showcases deals and even tried to get on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson.

I got some decent response but mostly I got rejection letters. I hooked up with an agent who supposedly had Crystal Gayle interested in one of my songs, but it never panned out. Right around then I got the job at Fender. I continued to play in bands. It really helped me at Fender to keep in touch with the reality of what most musicians need as opposed to the tiny percentage of stars’ needs.

And your interest in art? Influences?

John Page: To answer a question on “art” seems to imply that it’s something different than everything else I’ve done. I tend to look at all of the different things I’ve done as art, “functional art”, and I’ve been into that as long as I can remember. Just like designing and building guitars, surfboards, jewelry and museums, I don’t have any formal training in “art” either.

Every time I tried to take formal training in anything “creative” I was told you have to learn and follow the rules before you can break them. I was way too impatient for that. If I followed that rule I doubt that I would have accomplished what I have thus far in my life, and I plan on doing a lot more cool things before I’m done. I love to create, and I love to change canvasses.

As far as influences go, I really like: deco and tribal art; Antonio Gaudi’s architecture; Sam Maloof’s furniture; punk culture; “B” horror movies; jeez, there’re just way too many to think of, but I think you can see that it’s pretty diverse. I try to stay away from looking at (or listening to) any of the mediums I’m working on at the time. It keeps me honest. I don’t want to be too influenced by someone else’s work because I would feel like I would be ripping them off if I got too close to theirs – does that make sense?

When I was doing a lot of songwriting early on in my career, I remember waking up in the middle of the night and writing down a song I “wrote”. Lots of times I would hear the song later the next day on the radio. I thought I wrote it, but it was just stuck in the back of my head from hearing it before. So now I try to stay away from too many outside influences.

How did guitar making come about?

John Page: I got into guitar making because I didn’t have any money and I liked to design and build stuff. I built my first guitar when I was 13 or 14. I know this sound like bullshit, but I actually used a camping knife, a cheapy scroll saw and a file. I used some maple for the neck, but I didn’t know what rosewood was at the time, so I thought that cherry would be good for the fingerboard. It wasn’t.

My parents had all these abalone shells in their garden, so I swiped a couple of those and inlayed some birds in the fretboard. Something about trying to polish a turd I guess. I tore apart an old Tiesco del Ray for electronics, and the rest I forget. Anyway, the guitar turned out to be a total piece of shit, but it was my first and it made me try again, and again, and again. I ended up throwing it in a dumpster soon after I started working at Fender in 1978.

Like I said earlier, I have no formal training in anything I’ve tried, woodworking and guitar building included. My only woodshop training was in the 7th grade when it was mandatory to take it for a half of a semester. My only memory is the teacher sticking his fat finger in my ear saying “the book is wrong”. Obviously, I learned that much anyway. But I have no recall whatsoever of him teaching me anything related to woodworking.

Education?

John Page: I guess I started getting impatient in high school, so I thought I would quit after my sophomore year. I went up to Oregon and did a bunch of hiking and songwriting for awhile. Then it hit me – I was a dumb ass. So, I went back to continuation school because by that time I was working as a janitor in the local oil fields and I couldn’t go to school full-time. This way I could go three hours a week. The only bitch was that I had to go with all of the gangsters and loadies that got kicked out of every other school, so it was quite the experience – cat fights at lunch between girls with razor blades in their hair – ahhh, the Southern California lifestyle in the ’70s. After about six months of that I was able to go back to my old high school and graduate, with honors even. Crazy.

After that, I went to a couple of different colleges over about three-and-a-half years. I started with a music major and ended up with an engineering major. I quit about a year after Fender offered me the guitar design job in research and development. Again the term “dumb ass” comes to mind. All these years later I realize that as much as I loved to “learn”, I hated to be “taught”. But I must say, my teachers at Fender taught me things that no school could.

As far as early career goals, I wanted to be a famous musician. Again, the term “dumb ass” comes to mind.

Jobs before Fender?

John Page: Jobs before Fender – are you ready to be impressed? I was a janitor, starting at around 14-years-old, in the oil fields in Sante Fe Springs and Norwalk, California. Then I moved up to cleaning Carl’s Jrs. and other miscellaneous shitholes until I was 17. Then I took the major leap into fast food, where I worked at Pup ‘n’Taco, some steak house, and Jack-in-the-Box until I got this great job being a coffee machine serviceman. Bitchin’, huh?

Then, about a month before I got married the first time at 18, again “dumb ass” comes to mind, I started working at a metals and plastics warehouse in Los Angeles. That company was called E. Jordan Brookes Company and they had a company that they sold to every now and then called CBS Musical Instruments that in turn owned a little company called Fender.

What led to your job at Fender?

John Page: I had been at E. Jordan Brookes for about two years. I had worked my way up to assistant warehouse manager (whooo). One day in 1978, I got an order to fill for some .093” black delrin rod for CBS Musical Instruments. Well, I knew who that was, it was Fender Guitars. I started applying at Fender in 1973. I was 16 years old, and they kind of laughed. I think it was the leisure suit, though that might have been the time I applied in 1975, I don’t remember.

Anyway, I applied at Fender about five times prior to 1978, but when I got that order to fill, I thought I would apply again. I decided to take the day off – it was my birthday, May 9. I drove t

o Fender on my way to hang out at the beach for the day. I went into the personnel office and said hi to some guy that was standing there and then filled out an application. I turned in the application, went out to my truck, and started to drive away. Next thing I knew, the guy who I said hi to was running out to the parking lot waving me down. He stopped me and asked me to come back in.

Turned out he was this guy named Jerry Brock who was the general foreman at the time. He liked my application and wanted to talk to me, so we had this chat thang. I told him that I had been building musical instruments and related equipment for several years and that I was currently an assistant manager at this warehouse and that I had applied at Fender five times previously and that I would do any job they had just to get in the door. But, I had one caveat: I wanted to make sure that I could advance based on my efforts. He said there was plenty of room for advancement and offered me a job on the factory floor buffing guitar necks. I went from there to the beach, thought for a while, and then called him back to accept the position.

I had no idea of what I was getting into.

My first day working for Fender was May 21, 1978. I had this vision of Fender being a bunch of surfer type guys hanging around building guitars. I was wrong. This was a full-bore factory with full-bore factory workers, most of whom could care less that they were building a guitar. This was totally disheartening to me. I hated my job. In fact, on my first day I called my wife at the time to tell her that I had made a terrible mistake.

The job sucked and my boss, I won’t use his last name but his first was Art, was a flaming asshole. I didn’t know if I could stay. My co-workers were telling me to slow down ‘cause I was making them look bad, and nobody trusted me because Jerry Brock, the general foreman, kept coming by asking me how I was doing.

My “vision” of what Fender was couldn’t have been farther from the truth. What had I done? It wasn’t until later, much later, that I realized this was the “CBS corporate versus union mentality” that infested the factory – and the guitars.

Your career with Fender prior to the Custom Shop?

L-R: Steve Boulanger, Michael Stevens, John Page, Larry Brook – photo courtesy of John Page.

John Page: I kept working my ass off in neck buffing. I hit “standard” (the quantity and quality mandated by management) within two weeks. My co-workers were pretty pissed, but we started getting along anyway. I ended up meeting more and more people who really did care about the product.

Unfortunately, though, most of them were in no position to make a difference. The chasm between management and the factory workers was huge. I applied for every job posting that came up the first two months I was there. Finally one came up that I knew I was made for – model maker for research and development. I applied for it and got it!

I worked for a guy named Pete Bell who was head of the model shop and another model maker named Dave Moehler. I had such a cool gig. I built prototypes off of the drawings from the designers and engineers. I got to work with some really historical people like Freddie Tavares, Harold Rhodes, Ed Jahns – the list goes on and on.

And I didn’t just build guitars. I built amplifier chassis and boxes, piano parts, mixing consoles, drum parts – I even had to turn custom drum sticks – so it was very challenging and extremely interesting.

I guess about a year or so after I started in the model shop, Dave quit. About the same time, Pete took over new responsibilities and I was made supervisor of the shop. I hired long-time service center employee Steve Boulanger as the other model maker. He and I made a great team. Years later, when CBS laid off most of the employees, he would go on to Jackson and Valley Arts Guitars. I hired him into the Custom Shop in the late ’80s. He is a great tooling guy.

A year or so later, Greg Wilson, the guitar designer with Freddie Tavares, took a sales job in the field. He and Freddie recommended me to fill his spot. What a freakin’ honor, 23-years-old and I was made a guitar designer at Fender working side-by-side with Freddie Tavares – wow.

Freddie became like a father to me. He even called me his third son, no disrespect to his real sons, Terry and Freddie Jr. He taught me the ins and outs of guitar design, told lots of historical stories, made me take vitamins, and told lots and lots of really bad, old jokes. He would even do one-arm pushups when artists stopped by just to show them how spry he was. I loved him. What a great man.

John Page (Right) with his friend and mentor Freddie Tavares (Left) – photo courtesy of John Page.

My first design was the Bullet guitar – the Tele-looking one with the one-piece metal pickguard and bridge, not the sorry ass Strat wannabe one. That pickguard/bridge combo was my first U.S. patent, so that was kind of cool. The other one (Bullet) was from this guy from Peavey who came in for a few years – didn’t much care for him.

Anyway, it was a weird time at Fender. Most of the product was kind of sorry-ass. It had gone so far south that it couldn’t be turned around overnight, so it was a major transition period.

I worked with this guitar marketing manager, Paul Bugelski. He was a good guy. He was trying really hard to get the product turned around. In fact, he had already started the vintage reissue series before he was let go and Dan Smith came on. Paul never really got credit for it, but he had been working with Freddie on the Tele reissue in 1980.

I also had to design/spec some odd guitars, like the Walnut Super Strats and the Collector Series guitars. I try not to remember too much. When Dan came on board in 1981, he picked up the task and expanded the vintage reissues to include other instruments. We worked very closely and well together back then. We fought and disagreed a lot, but it was all good. We were a good team.

In the early/mid ’80s, Dan wanted to create the “next generation” of instruments, so we started to develop the Elite Series. This became another one of those embarrassing product lines: too many people inside trying to make a Fender guitar something other than a Fender guitar; trying to make it a Gibson/Yamaha/Peavey hybrid. It tanked. An interesting note: Most people don’t know that I designed the Performer bass as the Elite version replacement for the Jazz bass. Whew – I’m glad we didn’t take it that far.

Anyway, shortly after that, CBS put us up for sale and things got pretty crazy.

After Bill Schultz bought the company from CBS, my design duties virtually went away. He opted at the time to discontinue U.S. manufacturing and all of our product was made in Japan. I did some designing, but it failed to be challenging or fun. I did artist relations and wrote service manuals and I really got to hate it, so in February of 1986 I resigned to work on my music full-time.

Right before the Custom Shop is formed you took some time off from Fender?

The Waive. John Page (far right – photo courtesy of John Page.

John Page: I called it “my eleven month hiatus” because I still worked with Fender on a couple of consulting projects, and then I went back, but reality was that I had quit. I was about to turn 30 and I wanted to give my music career one last major push.

I had never worked on my music full-time, so I thought if I did, I’d be able to pull if off. I had also just married this wonderful woman, Dana. She convinced me that I should follow my heart and dreams and go for it. She told me if I wasn’t happy I should quit Fender and work on my music, so I did.

It was a financial struggle. She supported us and we lived in half of a converted garage, but we were incredibly happy. I worked on a couple of demos with some great musician friends of mine: Bill Giles on bass; Mark Myers on guitar; Rob Schwarz on keyboard; and, John Cermanero on drums. Tried to shop the demos, but they didn’t hit.

I remember near the end of the year I was talking to Elliot Easton from the CARS. We had become good friends over the years. I told him how disappointed I was that I couldn’t get any interest in my music. He told me that he thought we were born to do things that we’re special at. For him it was guitar playing and he said that I built some of the best guitars in the world, so I shouldn’t be bummed about it – just go back and do what I do best. His words of encouragement led me to go back to Fender and start the Custom Shop. I also learned two very important life lessons: Do what you believe in; and, success is measured by happiness, not money.

How did the Fender Custom Shop come about?

John Page: I called Dan Smith in December of 1986 to tell him I was going to get back in the guitar industry and asked him if they had any openings at Fender. He said that I could have my choice – get back into guitar R&D or get in on the ground floor of the Custom Shop. I really didn’t have any desire to get back into R&D (I didn’t get along very well with the guy in charge), but I liked the idea of the Custom Shop. Back when I was in the model shop, we made custom guitars for artists all the time. Fender just didn’t advertise it. In fact, John Cermenaro (Rogers drum designer), Steve Boulanger and Scott Zimmerman (model makers in R&D), and myself, put together a proposal for us to start a Custom Shop as outside vendors, back in 1984 -1985. The proposal was rejected by CBS management.

Anyway, it was a project that we had been talking about for years, but it just didn’t seem that the timing was right until now. Dan told me that they had been talking to Texas-based guitar builder Michael Stevens and that he had agreed to come on board so I could work with him if I wanted. It sounded good so I took the job.

The early years of the Custom Shop…

Custom Shop Softball Team, The Ver-Men – photo courtesy of John Page.

John Page: At the time, Bill Schultz’s vision of the Custom Shop he wanted was a couple of guys “out in the back forty” making a few really cool guitars a year. It would help raise the quality perception of Fender product. He wanted us to build a showplace, so we did.

We didn’t have a shop for the first few months of 1987, so Mike and I worked out of his house in Corona. We worked primarily on our walnut and ebony benches.

Bill said he wanted a showplace and we took him at his word. The walnut was actually left over from the Walnut Collector Series of guitars, so it finally went to something good.

After a few months, we finally got into our new area of the factory in Corona. It was an 850-square-foot niche – plenty of room for two builders.

Unfortunately, the original idea of what the Custom Shop should be changed very quickly. It was decided that we would build two kinds of product: actual one-off, hand built guitars and, “custom option” guitars. The latter would be factory instruments that we would modify with custom colors, hardware, pickguards, etc.

The orders started piling in – way more than we could handle, and we still weren’t done with the shop yet. After awhile, Bruce Bolen, who was the vice president in charge of the Custom Shop at the time, told us we had to start building some guitars. Just so we could get something out quickly, Bruce sold a custom version of one of the Japanese guitars they had in stock, just a custom color thing as I recall. I thought it was a sad statement for what we were supposed to be all about, but we had to do it.

Within a couple of months, we were told that we had to produce 30 guitars a month! Mike was an excellent builder, but he was very methodical and slow and he didn’t feel that he should have to budge from what he was hired to do – build a couple of great guitars a month. I have a great respect for that. Unfortunately, that didn’t quite work for a big company like Fender. They were used to changing their minds and expected their employees to go along with it.

At this point the pressure fell on me. Bruce made it pretty clear that if we didn’t start building 30-plus guitars a month, the shop would be closed.

One of the places we got the most interest from was Japan. Our distributor in Japan would order multiple pieces of several models they wanted. That was a good thing for me. I took those quantity orders and started making them in “quasi mass” limited runs of about 25 – 30.

Based on what Bruce said and what Mike could build, I had to build 28 guitars that next month. Then Bruce told me we had to raise the number to 40 guitars a month. That next month I had to build 38.

John Page with a Custom Shop maple stash. Photo courtesy of John Page.

I use the word “build” a little loosely. When you have that many guitars going, you have to rely on others to help a lot, so I would do critical steps and then pass it on to people in the factory to do other steps. It’s the only way I could handle the quantity that was being mandated.

After that, I couldn’t really take it anymore and I told them that we would have to hire some more help. We hired Fred Stuart as our first apprentice. He had been with Fender for awhile working on the tune-test line. He had been helping me here and there in the past, so he was a great addition.

Not too long after that, a builder by the name of Richard Syarto showed up. He had moved out to California from back East just hoping we would hire him. We finally did. So, by the end of 1987 there were four of us and we were already out of room and were way behind with our orders. A far cry from “the couple of guys in the back forty making a few cool guitars a year”.

Over the next couple of years we grew by leaps and bounds – added more builders and apprentices, more space, more machinery, and even new product lines like Kubicki. Those early years were incredibly hard. We all worked stupid amounts of hours, ‘cause we knew if we didn’t make it work, the shop would close. Everybody was right there with me. It was great. We would actually bring our sleeping bags the last days of the month so we could work late, sleep for a few hours, and then get up early and keep working.

Freakin’ great memories! I remember Fred Stuart sleeping on a pallet rack, John English bringing a camp stove and cooking us all breakfast, “inflatable love doll volleyball”, Jay Black trying to block it all out, and lots of other fun, great stories. We played hard because we worked so incredibly hard. I was so proud of all of those guys, and it was such a wonderfully unique experience.

The growth did have its cost though. After about two years, I had to give up my bench and stop building. Running the place, along with the constant expansion, left me no time to build. Shortly after that, Mike Stevens left Fender and went back to building his own guitars in Texas. Fortunately, there were a lot of great builders who had come on board to take our place and keep the shop growing.

Through the Custom Shop you got to work with several major artists.

(L to R) John Page, Eric Clapton and Freddie Tavares – Photo courtesy of John Page.

John Page: The artists were thrilled that they could finally have easy access to real Fender guitars made to their specs.

When Mike and I first started, before we even started making the walnut benches, we worked on the Eric Clapton Signature Model.

Dan Smith and George Blanda had already begun work on the early instruments, so when we started, we all pitched in to make the final versions and the ones that went to the trade show.

The second guitar out of the “official” Custom Shop was a custom lefty Telecaster Thinline I made for Elliot Easton. It was a maple neck, painted Surf Green with a white pickguard – very tasty. I used to build a lot for another lefty, Cesar Rosas [from Los Lobos], too . He would come by on the weekend with a six-pack of beer and we’d sit around and design guitars for him.

It was this totally relaxed atmosphere and the artists loved it. Mike knew Stevie Ray Vaughan pretty well, so he and I met with him and his tech Rene to develop his Signature series.

When Mike was in Texas, he had created these special calibrated pickups that he had done for Stevie. We ended up releasing them and called them “Texas Specials”. I think they’re still the most popular Custom Shop pickup out there. Touché, Mike!

Over the years, we worked with virtually ever artist that played Fender. In fact, the artist relations department moved out to our shop because the artists were all so interested in what we were doing. It was a great way to not only service them, but also get their input on all the products we were developing.

I remember a couple of cool stories. Merle Haggard came out to the shop. Builder Mark Kendrick went to the tour bus to greet him. Mark told Merle that he wanted to introduce him to the vice president of the Custom Shop [that was me]. Merle said that he better put a jacket on so that he looked respectable. When he came into my office and saw that I had shorts on, he said, “Shit, I don’t need to wear this jacket. This is my kind of place,” and went back to the bus to take it off. We were pretty relaxed.

Another time, Billy Gibbons came out. It was really late on a Friday night and most of us wanted to go home. He felt bad that he was late, so he brought us a bunch of Dad’s Root Beer, Abba Zabba bars, and hot sauce. You gotta love that. We just hung out and designed him some guitars.

The artists became part of who we were and what we did. If they weren’t so accepting and open with us, the shop would never have become what it did.

How did the Fender Custom Shop Art Guitars come about?

Custom Shop Stratocaster with artwork by Pamelina H. – Photo courtesy of Pamelina H.

John Page: The first “Art Guitar” I can remember was a Tele that John English did. I think it was inlayed with a Hawaiian theme. It was pretty cool. I think Steven Stills ended up buying it through our good friend Dan Martin at St. Charles Guitar Exchange.

Anyway, it seemed like a great way to take our product to yet another level, so, once or twice a year, I would let the builders design and build the guitar of their choice, primarily for trade shows. I think Fred Stuart took that to the limit. He kind of had the wackiest ideas. His trilogy of the Egyptian, Mayan and Celtic pieces were absolutely amazing. Alan Hamel’s matching Tele and cowboy boots were pretty cool as well.

But, it’s impossible to talk about the Art Guitars of the Fender Custom Shop without talking about Pamelina [Pamelina Hovnatanian, or simply, Pamelina H.]. She was my artistic partner and was “hands on” on countless projects. She had an uncanny way of “seeing” what was in my mind. Despite my incredibly bad sketches and babbling word pictures, she turned ideas into world-class pieces of art.

I first met Pamelina at a NAMM show sometime in the late ’80s. She had a backpack and a portfolio, and as I would soon find out, incredible talent and a gigantic set of balls. As I recall, she just walked up, introduced herself, pulled out her portfolio and said, “Hey, check this out! I want to do some work for you guys.” I used to get hit-up by artists all the time that wanted to do work for us at the Custom Shop, but none of their work ever “got” to me. Until Pamelina.

Even in these early years her work was spectacular… it just seemed to have a soul to it, you could feel the artist coming through. I knew I had to give her a try. In those early days she would come by the shop and I’d give her some bodies and say, “Do what you do,” and she’d go off and create these ultra-cool pieces. Some we sold and some we didn’t, but it was the beginning of an amazing relationship between two artists and created some historic product for the Fender Custom Shop as well.

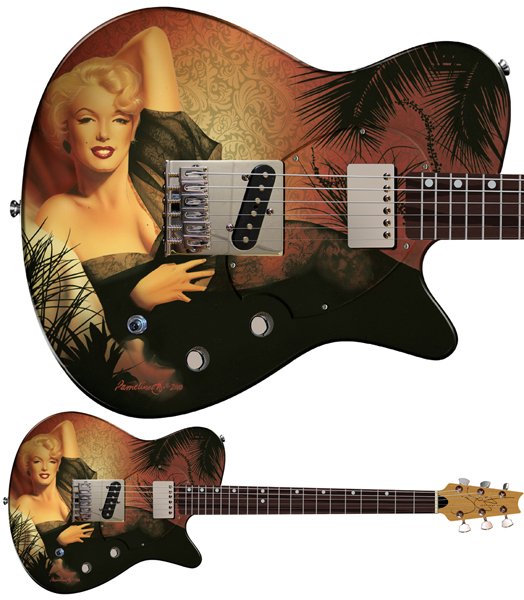

Just Marilyn Page guitar One of the guitars from the California-themed Pamelina and the Masterbuilders show. (Photos courtesy of Pamelina H.)

I could go on and on about all the projects we did together, the Harley Davidson Strat, the Playboy Strat and the Hendrix Monterey Strat, just to name a few. We developed a great love and admiration for each other over these years. Without her talent and inspiration, the Fender Custom Shop would not have been what it was then or what it is today.

I am very proud to have had the pleasure of working with her and prouder still to call her my friend. We continue to work on projects together. In fact, we’re planning on doing at least one P-1 art guitar together a year, starting in 2007, so the fun continues!

When George Amicay came on board, we added yet another cool dimension to our arsenal. As I recall, John English met George at a swap meet in Long Beach. George had just been laid off of his aerospace job and had started tinkering around with wood carving. He was amazing.

Photo Gallery – Special Bonus with John Page and his P-1 Guitar!

Photos courtesy of John Page.

|

|

Fender Museum, Corona, California |

|

|

“Here I am while I was drawing the P-1 body chamber details. Notice the extremely neat and clean filing system I have behind me!” |

|

|

“Here’s the old school method that Freddie Tavares taught me, after I draw the body, I get blueprints made, glue them to hardboard and then cut, file and sand, until the template is perfect. From there, I transfer rout the template to Baltic birch plywood. I use the birch ply templates in the shop and keep the hardboard originals as master templates in case the shop ones get damaged.” |

|

|

“There are at least two big, old, beastly things in this picture. In addition to that, here I am pin routing out the first P-1 proto body.” |

|

|

“Here’s a shot of the acoustic chambering on the P-1 body.” |

|

|

“The top being glued onto the chambered P-1 body.” |

|

|

“Peghead veneers getting glued onto the P-1 neck.” |

|

|

“John Page P-1 guitar” |

|

|

John with daughter Ashley and son Adam |

|

|

Ashley, Adam and John’s grandchildren |

|

|

John with his wife, Dana, at the Fender Museum |